Joan of Arc, Countess Emilia Plater, Wonder Woman: Singular women placed on a pedestal, carefully arranged and served on a silver platter of inimitable exceptionalism, meant to be admired for their sacrifice, but not duplicated. These are the flawed foundations of the stories of “heroic” women that have helped insure that the concept of the women warrior remains an anomaly more akin to a fictional superhero than an accepted reality.

By Victoria Martínez

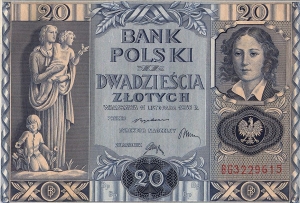

Polish poet Adam Mickiewicz immortalized her and insured her eternal fame in Poland with his 1832 poem, “The Death of a Colonel.” American feminist Margaret Fuller introduced her to the U.S. in her 1845 book, “Woman in the Nineteenth Century.” Now, in 2017, a spate of cursory popular history articles has brought the story of Countess Emilia Plater (1806-1831), a Polish noblewoman mythologized as Poland’s national heroine and frequently referred to as “the Polish Joan of Arc,”[1] to the attention of those with an easily quenched interest in history.

The problem is that these histories rely on a flawed narrative – one that is imbued with patriarchy and what Dr. Halina Filipowicz[2] called “a quasi-magic gesture of repetition.”[3] On the surface, these modern historical recaps seem to take a tone that evokes a sense of women’s empowerment and inspiration. In reality, they are breathlessly perpetuating trivialities that have been passed down over centuries to minimize the patent rejection of women who sought equality with men.

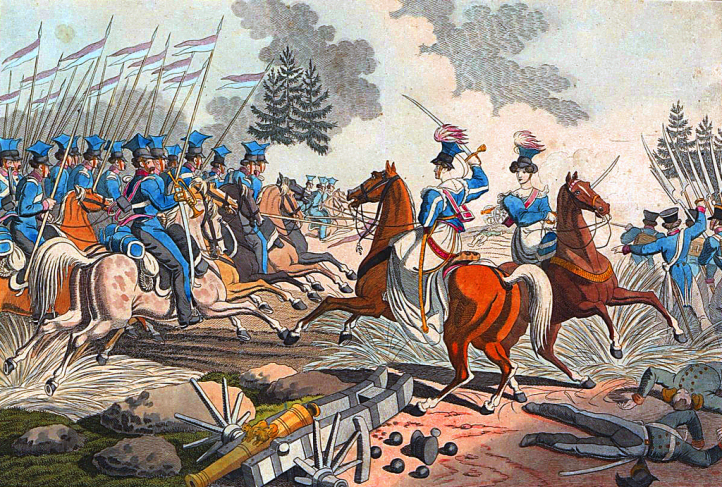

For instance, instead of focusing on the hostility that greeted Plater’s brief career as a woman warrior during the November Uprising of 1830 – a Polish and Lithuanian rebellion against Russian Imperial rule – these writers keep up the pretense that Plater was somehow a great success because she cut her hair short, wore men’s clothes, and excelled at “masculine” pursuits like fencing, riding a horse, and bearing arms, all so she could fulfill her lifelong ambition of fighting for her country. Her greatness, they imply, is that she overreached gendered expectations of women at the time in the name of patriotism – a device evident in “The Death of a Colonel”[4]:

“On a shepherd’s cot he is laid out —

In his hand a cross, by his head a saddle and belt,

By his side, a sword and a rifle.

But this warrior though in a soldier’s attire,

What a beautiful, maiden’s face had he?

What breasts? –Ah, this was a maiden,

Lithuanian born, a maiden hero,

The leader of the uprising, Emilia Plater.”[5]

Never mind that Plater was never a colonel, nor was she the leader of the uprising. These distortions of history pale in comparison with the faults created by androcentric history. The key in Mickiewicz’s narrative – which is perpetuated through modern histories that don’t scrutinize the bias or reach into academic analysis – is that her gender transgressions were done out of patriotic fervor, not a desire to achieve personal freedom as a woman or equality with men. This was a narrative designed to encourage others to similar patriotism, but discouraged women to answer the call through imitation of Plater.

It is at the heart of the larger issue of the manipulation of women’s histories to shape a narrative that invariably benefits the patriarchy. Rarely do these narratives raise the status of women in any tangible way or lasting way.[6] Instead, they are shaped to suit the cause, carefully leaving out the woman’s point of view and her (unadulterated) motivations. A woman’s duties are many, these narratives teach, and change with the political imperative. They are never a duty to put herself, her rights, her privileges, her responsibilities, etc., on an equal footing with men. Written by and for patriarchal societies, they ask women only to serve that system without question.

In Plater’s case, a narrative was created that artfully appeased women’s sensibilities and let them dream vicariously of doing the same, but reminded them that the actions weren’t what was important – only the sentiment: in this case, the sense of duty to one’s country.

In her 1996 analysis of plays featuring Plater, Dr. Filipowicz wrote, “[The plays] may seem to confirm the assumption that popular theater seeks to reach the widest approval by supporting preconceptions, not by subverting them.”[7] By failing to analyze and question the traditional narrative, these modern popular histories are doing the exact same thing.

As if regurgitating these narratives without any thought to what they are perpetuating isn’t bad enough, they are even worse when they posture as histories that inspire and empower women. Without a strong dose of context and historical reality, they are no better than the same trope they always have been. And they have the same effect on the unknowing or uninitiated: they blow a puff of air that briefly lifts the heart and then abruptly lets it fall again. There is no call to action, no road map for the aspiring woman to follow (save the clichés of disguising herself as a man, etc.), and no sense of any outcome other than glory in premature death. In short, there is nothing to give rationale to why what seems like it should be an inspiring story feels much more like a disappointing non-starter.

The reality is that a story like Plater’s is not a historical success story for women, at least in the sense that it has not effected an improvement in women’s status. In this way, Plater and her fellow female warriors – as brave and noble as they undoubtedly were – failed. They failed to achieve the respect and admiration of their brothers in arms. They failed to be treated like equals. They failed to break down the patriarchy that rejected them until they suited that system’s propaganda machine. They failed because they never stood a chance of being given a fair and equal chance or of receiving a fair and equal history to their male counterparts.

In what we like to think is a more enlightened age, we fail these women when we lap up anodyne histories without subjecting them to critical analysis. When we let the puff of wind inspire us for a second or two, then move on without wondering how and why such historical “victories” haven’t led to a society of gender equality where the story of a woman warrior is an everyday occurrence. Instead, women like Emilia Plater are still an anomaly.

Plater was and still is a “heroic example” that defies the low expectations set for women. The portrayal of her is still inherently sexist, even if that sexism is unintentional. The continued insistence on making the insipid and tenuous connection between Plater and Joan of Arc is just one way this occurs. The only similarity between the two women is that they have both been idealized as a “virgin hero.” Still, the comparison persists, perhaps because it reinforces the ideal of the singularity of heroic women in general, and of women warriors in particular.

In a year that has seen the advent of a new and improved Wonder Woman, it’s hard not to notice that women are still primarily encouraged to view brave women as exceptional ideals to be admired rather than emulated, and to accept as flattery even a tenuous association with an iconic woman. If you are a woman doing something that shows strength, courage or stamina (in other words, assuming qualities usually associated with men), you have surpassed the expectations of your sex and are now a Wonder Woman.

By comparison, how many “great” historical men have had their legacies inextricably entwined with – even virtually subsumed by – a predecessor with whom he actually had very little in common?

The result is, unsurprisingly, that women of the past are far less likely to be historically “great” on the weight of their own merits and/or without clear gender demarcation, just as modern women with notable achievements are not simply great women, but are lumped together with infantile delight as Amazonian superheroes.

In Plater’s case, she was identified with Joan of Arc to consolidate the idea that she was not an ordinary woman, but an extraordinarily unusual case that few women could ever hope (or should dare try) to duplicate. The danger in allowing this narrative of female exceptionalism to continue to perpetuate is that Plater and countless historical women like her remain man-made, not self-made, women[8] – a legacy that continues to hinder women today.

***

Image: Joan of Arc, Countess Emilia Plater, Wonder Woman

[1]The most even-handed of these recent popular histories in English is this one on the History Collection web site, mainly because it is one of the few to doubt the authenticity of many elements of the popular history.

[2] Professor of Polish, Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

[3] Filipowicz, Halina. “The Daughters of Emilia Plater.” Engendering Slavic Literatures. Ed. Pamela Chester and Sibelan Forrester. Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1996. 43.

[4] “Śmierć pułkownika” in Polish

[5] An excerpt of the full poem. Translation from: “Traditions of Patriotism, Questions of Gender” by Ewa Hauser in Genders 22: Postcommunism and the Body Politic (1995).

[6] Another good example of this was highlighted recently in the article, “The Short, Daring Life of Lilya Litvyak,” by Edward White in The Paris Review.

[7] Filipowicz 46

[8] Paraphrasing Filipowicz: “Mickiewicz’s poem has had an incalculable effect on Plater’s afterlife. She is still seen as a man-made, rather then self-made, woman.” (Filipowicz 44)

Do you have the full text of Mickiewicz’s poem? If so could you share it?

LikeLike

Hi Gail,

An English translation is in the book, “Genders22: Postcommunism and the Body Politic,” in the chapter, “Traditions of Patriotism, Questions of Gender,” by Ewa Hauser. You can see a preview of the book, including the poem, here: https://books.google.se/books?id=PbeNcASVwXkC&q=Death+of+a+colonel#v=snippet&q=Death%20of%20a%20colonel&f=false.

Victoria

LikeLike

[…] men,” either as a sort of natural extension of their roles as wives, daughters and mothers, or as anomalies whose contributions have been held up as singular examples meant to rally women to the cause, […]

LikeLike

I think that your interpretation is a bit over the top. There are many points, which are not entirely true, for example saying that “actions weren’t what was important – only the sentiment: in this case, the sense of duty to one’s country” was only applied to Polish woman at that time is quite funny; entire Polish society during partitions was absolutely crazy about the idea of patriotism and not only women was forced, or rather entitled, to have this sense of duty.

Another thing is the fact, that people who fought in that time (mainly men) became something closer to superheroes than simply people with great achievements in minds of Polish nation, and Emilia Plater is not even the most exagerrated case. Take Mickiewicz for example; great poet, sure, but his life would shock even someone without conservatist opinions. Still, he is thought as the greatest Polish poet and almost every citizien will praise his memory, majority without even the slightest idea how often his hero could be found in a brothel.

Finally, Plater and many women at that time didn’t think about fighting the patriarchy as much as fighting the opressors which invaded their country. Of course, many were involved in emancipation movement, but often for them it was another way to make their nation stronger during the partitions. Also, many knew that their freedom is entirely dependent on freedom of their nation – even if we imagine that women during that time were emancipated and had the same rights as men their situation would be still pretty terrible; as Poles they wouldn’t have many rights anyway. As history shows, this mindset was right.

LikeLike

Thank you for your comment. I appreciate how well thought out it is.

We can agree to disagree, of course, but I think you misinterpret the quoted portion in the first paragraph of your comment. I do not suggest that only women were encouraged to have a sense of duty. I do state that women’s sense of duty was expected to be inflamed by the story of Plater, but only insofar as the “proper women’s sphere.” So, my feeling is that Plater’s story was carefully crafted not to inspire women to duplicate her actions, but rather to inflame their patriotism in sentiment only, or at least in socially-restricted and -acceptable ways.

As for Plater not being the most exaggerated case, I would agree. However, my reason for addressing the issue of Plater is that modern writers of popular history articles appearing online are perpetuating the falseness and exaggerations of her story as created by Mickiewicz and others without a second thought. In doing so, they are doing a disservice on several levels.

You are right that Plater was not so much fighting the patriarchy as trying to fight the foreign oppressors, and I do touch on that in my essay. What I take issue with in terms of the patriarchy is how her story was manipulated by a patriarchal system to sound as if it was “women’s empowerment” when it was no such thing. These modern writers who then take that narrative and perpetuate it, also trying to make her into some sort of female super hero, are equally as bad, in my opinion. None of it offers true substance or meaning, and as such only inspires a sort of armchair admiration rather than a motivation to act and break barriers.

Thank you again for your interaction.

LikeLike

Great read, thanks

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] https://barricades.ac.uk/items/show/200, https://abitofhistoryblog.com/tag/countess-emilia-plater/, https://abitofhistoryblog.com/2017/10/24/countess-emilia-plater-and-the-perpetual-anomaly-of-the-wom…, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emilia_Plater, […]

LikeLike