Women played significant and important roles in the American Revolution. Many broke traditional gender roles and suffered as much as the men they served beside. Marauchie Van Orden’s bravery at the Battles of Saratoga in 1777 earned her the rank of soldier and the respect of George Washington.

By Victoria (Van Orden) Martínez and Jim Van Orden

At a young age, my father (and co-author of this piece) introduced me to the American television series M.A.S.H.[1], then in its early years of syndication. Instilled with a strong sense of female empowerment and an awareness that women had historically been deprived of equal opportunities, I embraced the character of Major Margaret Houlihan as more than “just” an army nurse. She was a soldier. Even if she wasn’t technically allowed in combat, there was no question in my mind that’s what she was.

Major Houlihan was a personally- and sexually-liberated and empowered woman who served her country just like her male counterparts, often on the front lines. She wasn’t meek or apologetic about her high rank, and she never shrank from exercising her authority. And yet she was a beautiful woman who put on lipstick, styled her hair, and looked great in her uniform. To a young me, this all made perfect sense. There was nothing amiss or problematic with the portrayal of the character.

It was only later I realized how wrong I was. Not in my perception of Major Houlihan or of how women were and could be. Her character was a soldier. So were many, many real women in history – including the women who inspired the fictional character – who served their countries during wars and other conflicts, even when they weren’t allowed to enlist or serve in combat.

Where I was wrong was in believing that this was an accepted perception, or – at least – one that was finally ready to be accepted. Even today, the historical characterization of women’s role in wars and other conflicts is usually that they merely “assisted the men,” either as a sort of natural extension of their roles as wives, daughters and mothers, or as anomalies whose contributions have been held up as singular examples meant to rally women to the cause, preferably by knitting more socks. We – father and daughter – take exception to this.

So, when I read recently that The Women’s Memorial in Washington D.C. is “trying to register every woman who has served in the U.S. armed forces” going back to the American Revolution, but currently has “only about 10 percent” of the some 3 million women who have served, my first thought was to whether there were any “Major Houlihans” in my family history. As it turned out, my Dad was way ahead of me.

Although I am not one of her direct descendants, I’m proud to say that Marauchie Van Orden Sperry (1758-1845), a soldier of the American Revolution, is one of the many extraordinary women in my extended family tree. My father, I discovered, feels the same. The great storyteller of our family, he wrote a wonderfully-interesting long piece on Marauchie, which I’ve adapted here.

His original piece included educated historical speculation that filled in the many gaps in the historical record while also providing rich vision into what she might have experienced. I have included some of these where I think they are particularly meaningful or significant. These portions are either italicized in their entirety or are otherwise clearly identified as speculative. The rest is part of the historical record, even if it is obscure. Our goal is to put her into the modern record, not as a woman who assisted the cause, but as the soldier that she was.

“Among the brave ones”

The dead and dying surrounded her… and lead musket balls barely missed her head as she dragged a wounded soldier by his arm into a ditch filled with mud and blood-red water.

The soldier’s stench—sweat-soaked uniform saturated with urine—was almost as bad as that coming from rotting corpses floating nearby. Exhausted and nearly starving, her last meal—moldy bread and brackish water—consumed days earlier, the young woman screamed in frustration. Her voice was barely heard above the din of 10,000 men engaged in hand-to-hand mortal combat.

“Someone give me a knife…now!”

As she examined the deep leg wound, a soldier placed a pick, an eighteen-inch-long metal shaft removed from the end of a musket’s barrel, in her hand. She forced the sharp end into flesh and slowly extracted the half-inch-diameter lead ball. Her patient gasped in pain and fainted.

Ripping long pieces of cotton from her dress, she cleaned the wound with styptic water poured from a canvas bag tied to her waist, and wrapped the cloth around his leg to stop bleeding. A soldier helped her drag the body across a field that was the center of furious fighting to a tent where wounded were treated. The soldier was lucky to survive… but his leg would be amputated later. Antiseptics and sterilization were unknown.

That was just one of many soldiers 23-year-old Marauchie Van Orden saved on September 19, 1777. She displayed similar bravery and life-saving skills during the final battle at Saratoga, New York, on October 7. By then, and after British General John Burgoyne and his men surrendered, more than 500 Continental Army soldiers had died. But the hard-earned American victory was considered the turning point in the Revolutionary War.

Although the historical record doesn’t provide us with any actual details of her bravery, it does remark quite poignantly that she “seems entitled to a record among the brave ones of the Revolution.”[2] This remark was made at the beginning of her entry in a 1902 book entitled, “A Record of the Revolutionary Soldiers Buried in Lake County, Ohio” (our emphasis). Far from a side note, her entry is as substantial as those of the men featured alongside her. Her entry in “The Official Roster of the Soldiers of American Revolution Buried in the State of Ohio,”[3] published in 1929, though shorter, also pays her respect among predominantly men.

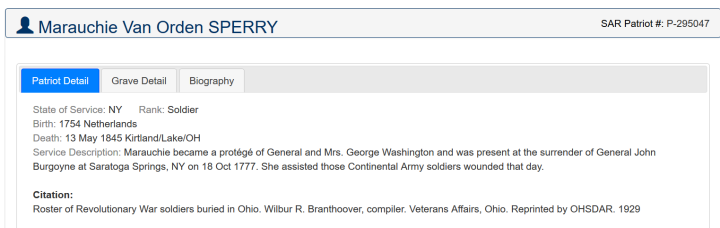

It is significant that both of these volumes include her as a Revolutionary soldier. It is not surprising that in both cases, the driving force behind this was the Daughters of the American Revolution. But it wasn’t only women who held her in particular regard. She holds the distinction of being one of only a handful of women Patriots of the Revolutionary War recognized by the Sons of the American Revolution.[4] Her profile notes her rank as “Soldier.”

From Immigrant to Soldier

Marauchie wasn’t born to be a soldier. The life she was born into in Holland in 1754 was a far cry from the life she experienced after she and her family immigrated to New York while she was still quite young. Described as “a wealthy family” with a “’substantial’ house of brick”[5] in lower Manhattan, their early life in New York would have been quite comfortable.

Despite growing British Army influence and occupation, life was good for New Yorkers in the early 1770s. However, bitter anger and rebellion among patriots accelerated as the decade progressed. General William Howe was given command of all British forces in America in early 1775 and led his troops to victory in the Battle of Bunker Hill.

A year later, he waged a bloody campaign to capture both New York City and Philadelphia. Patriots like the Van Orden family fought Howe’s troops in hand-to-hand, street-to-street combat. It would have been Marauchie and her family’s first—and tragic—taste of war.

The British surrounded the city, and the sheer number of well-equipped, disciplined soldiers eventually wore down the patriots. Conditions deteriorated in the days ahead when the British placed the city under martial law.

The Van Orden family and other patriots were now prisoners in their own homes. Food and water were scarce or non-existent. It was a war of attrition. The family would have been forced to survive by carefully rationing food stored in an underground cellar. They were fortunate to have a well that provided fresh water.

The well, however, turned out to be their undoing. Unbeknownst to the family, the British had poisoned every private well in the city – including theirs – with arsenic. Marauchie’s mother succumbed to the poisoning. At some point, the family managed to escape. The British burned their home and confiscated their estate.[6]

How they eventually escaped is not clear. In the end, however, only Marauchie survived. Her father and two brothers were killed fighting the British[7], leaving her alone in the world. Clearly, she had the strength within her not only to move ahead, but also to fight back against the forces who decimated her family and changed her life forever.

Somewhere along the way, she joined the Colonial troops. It’s possible she herself chose to march to the village of Saratoga, New York, when she learned General William Howe, who was responsible for her mother’s death, would bring his troops from New York City to join Major General John Burgoyne in leading the British assault there. Or maybe she was there completely by chance. We may never know. But she was there without question.

Saratoga—its name derived from an Iroquoian Indian word— was a tiny farm village on the banks of the Hudson River. Although the town was deserted and desolate, Continental Army forces led by General Horatio Gates and several thousand men of the Continental Army had built formidable defenses, including fortified walls on bluffs above the river to the north. Nearly two-dozen cannons were positioned along the walls and troops hid in strategic locations near roads.

On the first day of battle, September 19, Marauchie and the others were surprised by a column of General Burgoyne’s army that swept behind them and gave chase, musket balls ricocheting off trees, through the forest. Burgoyne had also deployed two other columns—one along the river from the north and another on roads from the east—to cut off arriving Continental soldiers.

The battle, which started at noon, grew with intensity as soldiers on both sides, hearing muskets, poured from the forest into fields surrounding the farm. As the afternoon progressed, the fight swayed back and forth, each force taking and retaking the field. Marauchie would have been swept into the conflagration as well. Fearlessly, she would have run to wounded soldiers and dressed their wounds, or carried pitchers of water to men who were thirsty or needed to cool cannon and musket barrels.

When evening approached, Burgoyne, perceiving his men had held the field, ordered a cease fire. This gave Americans sufficient time to fall back into the forest and regroup after dark. It turned out to be Burgoyne’s fatal mistake. The cease fire allowed his enemy to slowly build their ranks and become stronger. During the days that followed, while Burgoyne waited for additional troops from New York City and other areas to join his army, thousands of Americans arrived at Saratoga. Gates’ army was soon 13,000 strong.

Running out of supplies, time and manpower, Burgoyne was desperate. His 7,000-man army had lived on half-rations for weeks and winter was approaching. His second and most costly mistake, after losing several skirmishes in early October, was to consolidate his forces at Saratoga and set up a fortified camp for a final stand. Surrounded on all sides, his men starving and cold from constant rain, Burgoyne was forced to negotiate. He surrendered to Gates on October 17, 1777.

Unlike many previous battles, the Saratoga victory proved American troops could fight and beat a European army. It convinced the French to become American allies and fight the British, as well. Soon, the Dutch and Spanish joined the American cause. Now, instead of fighting a civil uprising, the British were forced to fight a world war on many fronts ranging from the Caribbean Sea to India. Historians later called the Battles of Saratoga the “turning point of the American Revolution.” They are also ranked among the top 15 battles in world history. And Marauchie had been in the thick of it.[8]

The Life of a Patriot

At the time, it was common practice for George and Martha Washington to take on protégés, also called aides-de-camp, who lived with them, received a small salary, meals and living quarters, and provided special capabilities or knowledge. Very skilled and brave soldiers served Washington as personal body guards, secretaries who penned his dictated orders and papers, and attended to his personal needs. Martha also had protégés who protected and accompanied her during public appearances. In private, they were her personal companions and liaisons with staff and officers assigned to the mansion.

Somehow, Marauchie became one of these protégés. Interestingly, history notes with a surprising lack of bias and assumption that, “She was a protégé of General and Mrs. Washington.”[9]

On April 19, 1779, in Danbury, Connecticut, Marauchie married Elijah Sperry, a 27-year-old widower and “Lieutenant of Artificiers,” a title given to a skilled or artistic craftsman. Born in Woodbridge, Connecticut, he grew up in New Milford and became a blacksmith’s apprentice at an early age. Sperry’s metal-working skills were in high demand when he enlisted in the Continental Army for three years in 1777. Starting as a corporal, he worked his way up to sergeant and then was promoted to lieutenant during the battles of Bennington (Vermont), Germantown (Pennsylvania), and Monmouth (New Jersey).[10]

Following their marriage, the couple relocated to West Point, New York, where Elijah “assisted in making and placing, across the Hudson River, huge chains to stop the British ships from supplying their forts up-river.”[11] According to the records, “Marauchie was there at the time the British ships attempted to pass.”[12]

Marauchie and Elijah had their first child together on January 16, 1780, and were blessed with eight more children between 1781 and 1797. They left the fort and service with the Continental Army in 1794 and built a small log house in Rutland, Vermont. Sadly, several of their children died during the ensuing years.[13]

Times were hard for Americans after the Revolutionary War ended in 1783. Young couples such as Marauchie and Elijah became the true “mothers and fathers” of the fledgling nation. They had to organize new local governments, build homes and communities, raise crops and livestock for food, and manufacture goods formerly imported from Europe.

Compounding matters for the Sperrys, Continental Army soldiers such as Elijah had been promised military pensions they never received (Marauchie, of course, wouldn’t have expected to receive anything herself). Marauchie’s SAR Patriot profile outlines the long struggle to obtain Elijah’s pension, starting in 1818, when he forwarded required documents to Washington, D.C. Months later, his application was rejected and returned because records of his military service had been destroyed in a fire. Elijah died that year at age 68 before the issue was resolved.

After Elijah’s death, Marauchie, who now called herself “Polly,” moved with several of her surviving children to Kirtland, Ohio. She applied for a pension based on her husband’s service at the Geauga County Courthouse. Unfortunately, the government official who kept Elijah’s pension records on file somehow lost them and then died. Marauchie testified in court that she had seen her husband’s military commission and discharge papers, but didn’t know what had become of them.

Finally, in 1835, the U.S. Department of Pensions accepted Elijah’s record of service but wanted proof that the Sperry marriage had been performed in 1779. She then encountered another challenge: the Danbury, Connecticut, clerk could find no record of the marriage because the town had been burned and all its records destroyed. It was thought a copy of the marriage certificate had been placed in a family Bible, but the daughter who owned the Bible told Marauchie the document had been lost.

Miraculously, and for reasons unknown, the U.S. Government decided to award Marauchie a pension and she was “inscribed on the Roll of Pittsburgh at the rate of $115.50 per annum to commence on the 4th day of March 1836.”[14]

Marauchie lived on her husband’s military pension for another nine years. She passed away on May 13, 1845, at the age of 87. In a time when 60 percent of the population never reached 20 years of age, she was a marvel. She was buried in “The Angel Cemetery” near Mitchells Mills Road in Kirtland, Ohio.

Ironically, after her death the government realized it had made a mistake calculating Elijah’s pension and owed her money.[15]

The real mistake, however, was that she herself had not been recognized as a soldier and Patriot in her own right until long after she was gone, and even then only in a limited way.

***

Main image: Burgoyne’s surrender at Saratoga by Percy Moran, circa 1911 (courtesy Library of Congress); overlaid by an image of the “Libertas Americana” medal commissioned by Benjamin Franklin and executed by Augustin Dupré in 1783 (Creative Commons).

[1] The show was about the doctors and nurses of a Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH) unit stationed in South Korea during the Korean War, and aired from 1972-1983.

[2] A Record of the Revolutionary Soldiers Buried in Lake County, Ohio. New Connecticut Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Columbus, Ohio: The Champlin Press, 1902, 55.

[3] The Official Roster of the Soldiers of the American Revolution Buried in the State of Ohio. Ohio Adjutant General’s Dept. (Daughters of the American Revolution, Ohio. Columbus, Ohio: The F.J. Heer Printing Company, 1929, 346.

[4] See the record of Marauchie Van Orden Sperry at the Sons of the American Revolution website.

[5] “Elijah and Marauchie Van Orden Sperry” at The Connecticut Society of the Sons of the American Revolution website.

[6] A Record of the Revolutionary Soldiers Buried in Lake County, Ohio, 55

[7] ibid

[8] ibid

[9] See: A Record of the Revolutionary Soldiers Buried in Lake County, Ohio, 55; “Elijah and Marauchie Van Orden Sperry” (Connecticut Society of the Sons of the American Revolution); “Marauchie Van Orden SPERRY” (Sons of the American Revolution).

[10] A Record of the Revolutionary Soldiers Buried in Lake County, Ohio, 55

[11] “Elijah and Marauchie Van Orden Sperry” (Connecticut Society of the Sons of the American Revolution)

[12] ibid

[13] Traces of the couple and remaining children weren’t found until the 1810 census. It revealed they lived in Luzerne, New York.

[14] “Marauchie Van Orden SPERRY” (Sons of the American Revolution)

[15] “Elijah and Marauchie Van Orden Sperry” (Connecticut Society of the Sons of the American Revolution)

Great story! She deserves her place in history as a soldier, and a place in the history of emergency medicine in this country as well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! She absolutely does!

LikeLiked by 1 person

An ancestor of mine, Dr. Caleb Sweet (1743-1798), served in the regiment of Colonel Goose Van Schaick (First New York) 1779 /1781. His title was Surgeon and he served under Washington. It’s conceivable that he and Marauchie might have met, through either medical work or their acquaintance with the Washingtons. Fun thought!

LikeLiked by 1 person

How wonderful!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lovina Sperry, the daughter of Elijah & Marauchie, married Obediah W. Call – who was a brother of my son’s g-g-g-g-g grandfather, Rufus Call, who also lived in Lake County, Ohio.

I think that qualifies as extended family?? Thanks for the wonderful write up.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fantastic! Thank you so much for this note and the connection. ❤️

LikeLike

Wonderful article! I was excited when I came across this after a Google search. I am a direct descendant of Elijah and Marauchie. What I have known about them comes from a photocopy of a short newspaper article published many years ago, but I have visited the cemetery and seen the headstone. I look forward to sharing this with my family.

Sincerely,

Laura Sperry Johnson

Willoughby, Lake County, Ohio

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the message, Laura! I’m so glad to hear from you, and I hope your family enjoys the article as well. All the best and Happy New Year!

LikeLike