From a former slave to two Nobel laureates, a selection of women writers in modern history and their often-overlooked narratives of Christmas.

Victoria Martínez

In modern history, the story of Christmas has been written across cultures, social classes, and time, even if the narratives written by those with little power have often been drowned out by those with the lion’s share. The following is just a small sampling of some of the women of diverse backgrounds and nationalities who, throughout the 19th and 20th century, wrote the story of Christmas. These stories, like the women who wrote them, resonate through the ages, and arguably deserve a far more prominent place in both historical and literary traditions than they currently enjoy.

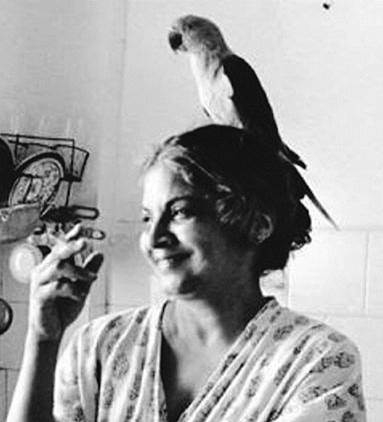

Elizabeth Harrison & Eunice de Souza – Views of Christmas Selfishness

Neither their time on Earth nor their cultures overlapped, but American educator and writer Elizabeth Harrison (1849-1927) and Indian professor and poet Eunice de Souza (1940-2017) both wrote of Christmas as a time when hypocrisy and selfishness was rife.

As a pioneer of early childhood education in the United States, Elizabeth Harrison “worked to teach parents and teachers the value of creative arts in child development and founded a teacher training program that became a model for the profession.”[1] In 1886, she founded in Chicago, Illinois, “a college to train women to teach kindergarten primarily in immigrant communities,”[2] that evolved into what is now called National Louis University. Her efforts laid the groundwork for the National Parent Teachers Association (PTA), and her books guided and advised parents and teachers on how to raise and educate young children.[3]

In her 1902 book, Christmas-tide, she pulled no punches when she wrote:

…how, as a rule, are children taught to observe [Christmas]? Usually by expecting an undue amount of attention, an unlimited amount of injudicious feeding, and a selfish exaction of unneeded presents; thus egotism, greed, and selfishness are fostered, where love, generosity, and self-denial should be exercised.[4]

Across time and space, it’s as if the children Harrison described had grown into the adults Eunice de Souza targets in her poem, Feeding the Poor at Christmas, which was published in her 1979 volume entitled Fix. Written in the voice of a wealthy woman who, joined by her husband, grudgingly fulfills a social obligation, the poem in its entirety reads:

Every Christmas we feed the poor.

We arrive an hour late: Poor dears,

like children waiting for a treat.

Bring your plates. Don’t move.

Don’t try turning up for more.

No. Even if you don’t drink

you can’t take your share

for your husband. Say thank you

and a rosary for us every evening.

No. Not a towel and a shirt,

even if they’re old.

What’s that you said?

You’re a good man, Robert, yes.

beggars can’t be, exactly.[5]

As a Goan Catholic[6] living in Mumbai, India, de Souza’s criticism was an expression of her “slow burning fuse about my community,”[7] whose so-called charity she perceived as both superficial and conditional. De Souza, who was a professor and head of the Department of English at St. Xavier’s College in Mumbai, frequently satirized patriarchal structures in her poetry. A feminist in post-colonial India, “Her candour and bold pronouncements on power and position reflect resistance literature to fight gender constraints.”[8] It is significant that she employed Christmas to highlight the ways both men and women use patriarchal domination to marginalize and oppress others.

Just as significant is the fact that, as a Third World woman who wrote in English, she contributed a much-needed diverse perspective to the predominantly Anglo- and Euro-centric Christmas narrative.

Fanny Jackson Coppin & Fannie Barrier Williams – Freedom and Fairy Tales

Like Third World women, American women of color have written narratives of Christmas, though few of these stories have been incorporated into the mainstream of literature, not to mention tradition. In the decades following the American Civil War, for instance, African American women were writing the story of Christmas in a way that is not yet sufficiently recognized. Fanny Jackson Coppin (1837-1913), who was born into slavery, and Fannie Barrier Williams (1855-1944), who was not, are just two examples.

Fanny Jackson Coppin was a remarkable woman. Born a slave, she gained her freedom when an aunt purchased it. While working as a servant, she actively sought an education so she could in turn educate other African Americans. She was more than successful in this endeavor. In 1869, she became the first African American woman to become a school principal, a position she maintained for more than 35 years at what is now Cheyney University of Pennsylvania.

Coppin’s writing included the 1880 short story, A Christmas Eve Story, originally published in the Christian Recorder in December of that year. Recently republished in a reprint of the anthology, A Treasury of African American Christmas Stories, the story is “…written in the style of a fairy tale with an appeal to very young readers and listeners,” according to scholar Bettye Collier-Thomas, and “…reflects [Coppin’s] concerns for poor black children and illustrates the plight of many she came in daily contact with in the alleys and hovels where they resided in Philadelphia.”[9]

The fairy-tale aspect of the story is heartbreakingly evident in the happy ending of two young black children suddenly orphaned on Christmas Eve and brought by a kindly policeman to the home of “Grandma Devins” for temporary shelter. Because the children were black, they were to be taken the following day to an almshouse, where they would have been among adults, including criminals. Had they been white, they would instead have been placed at an orphanage, where at least they would have been among children.[10] The fairy tale-ending comes when Grandma Devins proclaims, “…these children are my Christmas gift, and please God I’ll be mother and father both to the poor little orphans.”[11]

Like Coppin, Fannie Barrier Williams was also an educator, as well as a women’s rights activist, and one of a handful of African American women who played a role in both the black and the mainstream women’s suffrage movements in America. She was a co-founder of the National League of Colored Women in 1893, the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) in 1896, and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909.

Williams was also a writer, and her 1902 short story entitled, After Many Days: A Christmas Story, which was originally published in Colored American Magazine, offers a conjuring of ghosts that rivals those in Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. When a Christmas party brings her long-lost, bi-racial granddaughter to the home of the wealthy Southern family for whom she works as a servant, former slave “Aunt Linda” discovers that, “The shadow of the departed crime of slavery still remained to haunt the generations of freedom.”[12]

Having passed for white for many years, and unknowing of her own bi-racial heritage, young Gladys Winne is shocked to discover the truth revealed by her grandmother. Though the story ends with Gladys revealing to her white fiancé the truth about her heritage to the accompaniment of, as the moving prose of the story reveals, “… the magnificent voice of the beautiful singer rises in the Christmas carol…”,[13] the heart of the story lies with Aunt Linda. In revealing the truth she had held for so long she found the gift of true freedom:

For the first time and for one brief moment she felt the inspiring thrill and meaning of the term freedom. Ignorant of almost everything as compared with the knowledge and experience of the stricken girl before her, yet a revelation of the sacred relationships of parenthood, childhood and home, the common heritage of all humanity swept aside the differences of complexion or position.[14]

Juliana Horatia Ewing & Emilia Pardo Bazán – Singular Fantasies

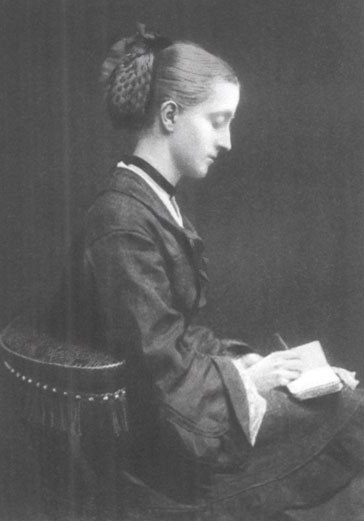

English writer and social critic Juliana Horatia Ewing (1841-1885) and Spanish writer, aristocrat and feminist Emilia Pardo Bazán (1851-1921) were both prolific authors whose oeuvre include distinctive Christmas “fantasies.”

Children’s author Juliana Horatia Ewing was the daughter of writer Margaret Gatty (1809-1873), who encouraged her daughter’s abilities as a writer and storyteller. Though her significant body of work was written for children and are often described as fairy tales, Ewing’s stories were written with a purposeful edge. According to Professor of English Laurence Talairach, “In most of them, fantasy acts as a means to refract the bleak aspects of women’s lives, as in ‘Christmas Crackers’.”[15]

Ewing’s Christmas Crackers: A Fantasia was originally published in December 1869 in Aunt Judy’s Magazine, a monthly children’s magazine edited by her mother, and reprinted in 1870 in the volume, Lob Lie by the Fire, the Brownies and Other Tales. One modern analysis of the story notes that it “…dare(s) to mock the hypocrisies of a revered Victorian legend, Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol,” and “…twist(s) the socialization of Dickens’s crusty miser, Ebenezer Scrooge, into less therapeutic enchantments.”[16] Critical reading of the story confirms what others have noted, that it hardly seems like it’s intended for children. “’Christmas Crackers’ is a rare evocation of the occult confusion, the tinge of demonism, that underlay the institutionalized fun of a middle-class Victorian Christmas.”[17]

Granted, these elements would very likely have been lost on a young audience, though perhaps not on any adults who happened to read the story. But the narrative is filled with elements that subtly critique traditional gender and social roles and normalize more progressive ones. For instance, the characters of the widow, who “had married a Mr. Jones, and having been during his life his devoted slave, had on his death transferred her allegiance to his son,” and said son, whom the widow had named Macready, but who was called by his cousins “MacGreedy,”[18] reveal a domestic folly borne out of tradition. On the other hand, one of these cousins, Miss Letitia, who “was as neat as a new pin, and had a will of her own,”[19] is relatable and unapologetic. At one point in the story, MacGreedy chokes slightly on a raisin, and the two women reveal themselves:

The widow tried in vain to soothe him with caresses, but he only stamped and howled the more. But Miss Letitia gave him some smart smacks on the shoulders to cure his choking fit, and as she kept up the treatment with vigour, the young gentleman was obliged to stop and assure her that the raisin had “gone the right way” at last. “If he were my child,” Miss Letitia had been known to observe, with that confidence which characterizes the theories of those who are not parents, “I would, &c., &c., &c.;” in fact, Miss Letitia thought she would have made a very different boy of him—as, indeed, I believe she would.[20]

In Spain, Emilia Pardo Bazán published at least two volumes of short stories dedicated to Christmas, Cuentos de Navidad y Año Nuevo (Short Stories of Christmas and New Year) in 1893, and Cuentos de Navidad y Reyes (Short Stories of Christmas and Kings) in 1902.[21] Like Juliana Horatia Ewing, Bazán also used the word fantasy (Fantasía, in Spanish) to subtitle four of her stories in the earlier volume, Cuentos de Navidad y Año Nuevo. And what a fantasy it is. Each of the four stories follows a woman being given a tour of a different place of the Afterlife on Christmas Eve: Hell, Purgatory, Limbo, and Heaven.

Her supernatural guide – a poet she once knew who had committed suicide years earlier – takes her first to Hell, where he remarks: “So that you see how mercy is not banished from Hell itself, I bring you to it the only night of the year when sinners are not tormented.”[22] Next, in Purgatory, the poet-guide explains that though the fire of hell is never visible, it burns inside. “…[T]here is a fever that never goes away … except tonight,” he explains. “A fever of forty-one degrees and several tenths, which dissolves the blood, dries the heart, scorches the mouth, sets the brain ablaze and breeds continuous delirium.”[23]

In Limbo, the protagonist shakes off her guide and discovers the great Napoleon Bonaparte as a child, who takes her to see a room filled with children playing manically. “It amazed and saddened me to consider such flowering of frozen buds before opening, so many green fruits damaged by the hail, so many empty cradles, so many desperate mothers.”[24] Here, as the child Napoleon explains that, “Only today, Christmas Eve, at the time that Christ was born, we see something real, something that is neither a hoax, nor theater decoration…,”[25] she realizes:

That human life expressed with toys, with puppets stuffed with sawdust, with cardboard and cheap paints, with doggerels and cards, must have become intolerable because of its petty falsehood. It was the insipid, the lie without veils of illusion, the abstract, the glacial, the inert, which neither fills the heart nor appeases the instinctive thirst to live…[26]

Finally, on entering Heaven, she feels a joy that “came mainly from the imagination, because I was not experiencing any positive benefit, but to think that one is in Heaven is already half of Heaven, or more than half.”[27] After witnessing the birth of Christ, however, she felt blinded to human realities by both clarity and light, only to be told by her guide, “That light that blinds you comes from your imagination, it arises from you. There is no such radiance.”[28]

Selma Lagerlöf & Grazia Deledda – Two Nobel Laureates

Swedish writer Selma Lagerlöf (1858-1940) became the first woman to win the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1909, “in appreciation of the lofty idealism, vivid imagination and spiritual perception that characterize her writings.”[29] Seventeen years later, in 1926, Italian writer Grazia Deledda became the second woman to win the award, “for her idealistically inspired writings which with plastic clarity picture the life on her native island and with depth and sympathy deal with human problems in general.”[30] Though both women are best known for work other than their writings on Christmas, the sentiments expressed by the Nobel committee perfectly describe these lesser-known works.

Selma Lagerlöf wrote several Christmas narratives, but it is perhaps her short story, “Legenden om julrosorna,” which was first published in Sweden in 1908, the year before she won the Nobel Prize, that best embodies the characteristics described in her selection for the award. The story was afterward quickly translated, and was first published in English in 1910 as “The Legend of the Christmas Rose.”

With her “vivid imagination,” Lagerlöf wove a descriptive tale of 12th century Scandinavia and the imaginary origin story of the flower Helleborus niger, known as the Christmas Rose for its tendency to bloom in snow. Her “lofty idealism” is evident in the message that grace, beauty and spirituality are not the sole property and domain of those who are ostensibly nearest to God; and that those with such a claim to the Almighty can destroy grace, beauty and spirituality through conceit and lack of faith. Finally, she demonstrates her “spiritual perception” in the prose that shines even in translation.

The glory now nearing was such that the heart wanted to stop beating; the eyes wept without one’s knowing it; the soul longed to soar away into the Eternal. From far in the distance faint harp tones were heard, and celestial song, like a soft murmur, reached him.

Abbot Hans clasped his hands and dropped to his knees. His face was radiant with bliss. Never had he dreamed that even in this life it should be granted him to taste the joys of heaven, and to hear angels sing Christmas carols!

But beside Abbot Hans stood the lay brother who had accompanied him. In his mind there were dark thoughts. “This cannot be a true miracle,” he thought, “since it is revealed to malefactors. This does not come from God, but has its origin in witchcraft and is sent hither by Satan. It is the Evil One’s power that is tempting us and compelling us to see that which has no real existence.”[31]

Grazia Deledda wrote her short Christmas story, Il Dono di Natale (The Christmas Gift), in 1895, 31 years before she won her Nobel Prize. The Italian island of Sardinia where she was born was the setting for most of her writing, even after she made Rome her home. Despite a severely limited formal education, she educated herself through her extensive reading, and dreamed of becoming “for Sardinia what Tolstoy was for his people: the observer and epic singer of his country.”[32]

Though Il Dono di Natalie is rarely mentioned in analyses of her work, it answers in every way to the winning attributes ascribed to her by the Nobel committee that have generally been associated with her later writings. The work, which is translated to English at Parallel texts: Words reflected, is truly an “idealistically inspired writing” considering how she honors the people of Sardinia in the story, despite the abuse many of them hurled at her for being a writer,[33] as well as her lifelong rebellion against the patriarchy and male authority so embedded in the culture.

On Christmas Eve, a family of poor shepherds prepares to welcome the well-off fiancé of the only daughter. With the patriarch of the family recently deceased, her brothers, “all strong and handsome, with black eyes and black beards, and were fitted in armor-like waistcoats, worn under sheepskin coats,”[34] attempt to fill his shoes. Deledda writes of them and all the men in the story with tremendous respect, while at the same time, in the words of the Nobel Committee, “pictur[ing] the life on her native island.” In particular, what it was like at Christmas.

His house really did smell of the festivities: it smelled of baked apple cake, and of cookies made with orange peels and toasted almonds; and Felle found himself gritting his teeth, as if he were already gnawing at all those things, delicious but still hidden from sight.[35]

And,

Inside the church, the illusion of spring continued: the altar was decorated with branches of strawberry tree covered in red berries, of myrtle, of laurel; the candles shone among the foliage, and the shadows it created were outlined on the sides, like on the walls of a garden.[36]

Ultimately, however, it is Deledda’s deftness at dealing “with depth and sympathy… with human problems in general” that truly shines. In this, it is again a male character – Felle, at age 11, the youngest brother of the family – who becomes a conduit for the best of her writing. Felle’s excitement over the unusually extravagant Christmas feast laid out thanks to his sister’s wealthy fiancé is tempered only by his faith and genuine concern for his poorer neighbors. Contemplating his family’s good fortune, Felle wonders with uneasiness, “But what sort of feast will our neighbours have with just a few raisins, while we have these two fine animals? And the cake, and the sweets?”[37]

Felle’s concern foreshadows the conclusion of the story as he returns home from the Christmas Eve Mass:

Felle walked as if he were in a trance, and he didn’t feel the cold; if anything, to him, the white trees that rose around the church looked like they were covered in almond blossoms. He felt, under his woolly clothes, as warm and happy as a lamb in the May sun; his hair, cold from the snowy air, seemed to be made of grass. He thought of all the good things he would eat after the mass, in his warm house; but remembering that Jesus was born in a cold manger, naked and without food, made him feel like crying, like swathing him in his own robes, and bringing him home with him.[38]

To everyone reading this, and especially to all who have followed my research and writing this past year, I wish a joyous holiday season and, to those who celebrate it, a very merry Christmas. And please be sure to explore the links in the text and the endnotes below for further reading on all of the women and works highlighted in this article. -Victoria

***

Featured image: Reading at a Table (1934) by Pablo Picasso, The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Image by Wally Gobetz).

[1] Peltzman, Barbara Ruth. Pioneers of Early Childhood Education: A Bio-Bibliographical Guide. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1998, 55.

[2] “Our History.” National Louis University. Accessed 12/18/2018.

[3] An example of her writing on education is her 1898 book, Why Kindergarten Matters.

[4] Harrison, Elizabeth. “Christmas-tide” (1902). Elizabeth Harrison’s Writings. Book 18, 41-42.

[5] de Souza, Eunice. A Necklace of Skulls: Collected Poems (Kindle Edition), Penguin UK, 2009.

[6] Roman-Catholics from Goa, India.

[7] Quoted in “Eunice de Souza.” Poetry International Web. Accessed 12/18/2018

[8] “Eunice de Souza: In her own words” The Navhind Times, Aug. 6, 2017. Accessed 12/18/2018.

[9] Collier-Thomas, Bettye, ed. “Introduction.” A Treasury of African American Christmas Stories. Boston: Beacon Press, 2018, 22.

[10] For more on this, I suggest “Orphanages and Orphans” by Holly Caldwell (2017) for The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. Accessed 12/18/2018.

[11] Collier-Thomas 24

[12] Williams, Fannie Barrier. “After Many Days: A Christmas Story”, reprinted in Elizabeth Ammons, ed., Short Fiction by Black Women, 1900-1920, New York: Oxford University Press, 1991, 225.

[13] ibid 238

[14] ibid 225

[15] Talairach-Vielmas, Laurence. Moulding the Female Body in Victorian Fairy Tales and Sensation Novels. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2007, 67.

[16] Auerbach, Nina and U.C. Knoepflmacher, eds. Forbidden Journeys: Fairy Tales and Fantasies by Victorian Women Writers. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014, 129.

[17] ibid 131

[18] Ewing, Julia Horatia. “Christmas Crackers: A Fantasia.” Lob Lie-by-the-fire, The brownies, and other tales. New York : Frank F. Lovell & Co., 1886, 293.

[19] ibid 295

[20] ibid 297-8

[21] Unfortunately, neither volume has been translated to English, at least as far as I have discovered.

[22] Bazán, Emilia Pardo. “La Nochebuena en el Infierno.” Cuentos de Navidad y Año Nuevo. 1893. Sourced from Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes. Accessed 12/18/2018. Personal translation.

[23] Bazán, Emilia Pardo. “La Nochebuena en el Purgatorio.” Cuentos de Navidad y Año Nuevo. 1893. Sourced from Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes. Accessed 12/18/2018. Personal translation.

[24] Bazán, Emilia Pardo. “La Nochebuena en el Limbo.” Cuentos de Navidad y Año Nuevo. 1893. Sourced from Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes. Accessed 12/18/2018. Personal translation.

[25] ibid

[26] ibid

[27] Bazán, Emilia Pardo. “La Nochebuena en el Cielo.” Cuentos de Navidad y Año Nuevo. 1893. Sourced from Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes. Accessed 12/18/2018. Personal translation.

[28] ibid

[29] The Nobel Prize in Literature 1909. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Media AB 2018. Accessed 12/19/2018.

[30] The Nobel Prize in Literature 1926. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Media AB 2018. Accessed 12/19/2018.

[31] Lagerlof, Selma. The Legend of the Christmas Rose. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran and Co., Inc., 1910, 24.

[32] Amoia, Alba. 20th-Century Italian Women Writers: The Feminine Experience. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1996, 5.

[33] ibid 6

[34] Deledda, Grazia. “Il Dono di Natale” 1895. Translation by Matilda Colarossi, available at Parallel texts: Words reflected, accessed 12/19/2018.

[35] ibid

[36] ibid

[37] ibid

[38] ibid

Victoria — You really did some impressive research to find all these unusual stories! Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And I loved every minute of it. ❤️😊 Thank you, Jan!

LikeLike

Wonderful article and impeccable research. Thank you for it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Patricia!

LikeLike