While the Green Book has become something of a buzzword lately thanks to Hollywood, the “mother” of the essential guide for African Americans navigating Jim Crow America has been overlooked and all but lost to history.

Victoria Martínez

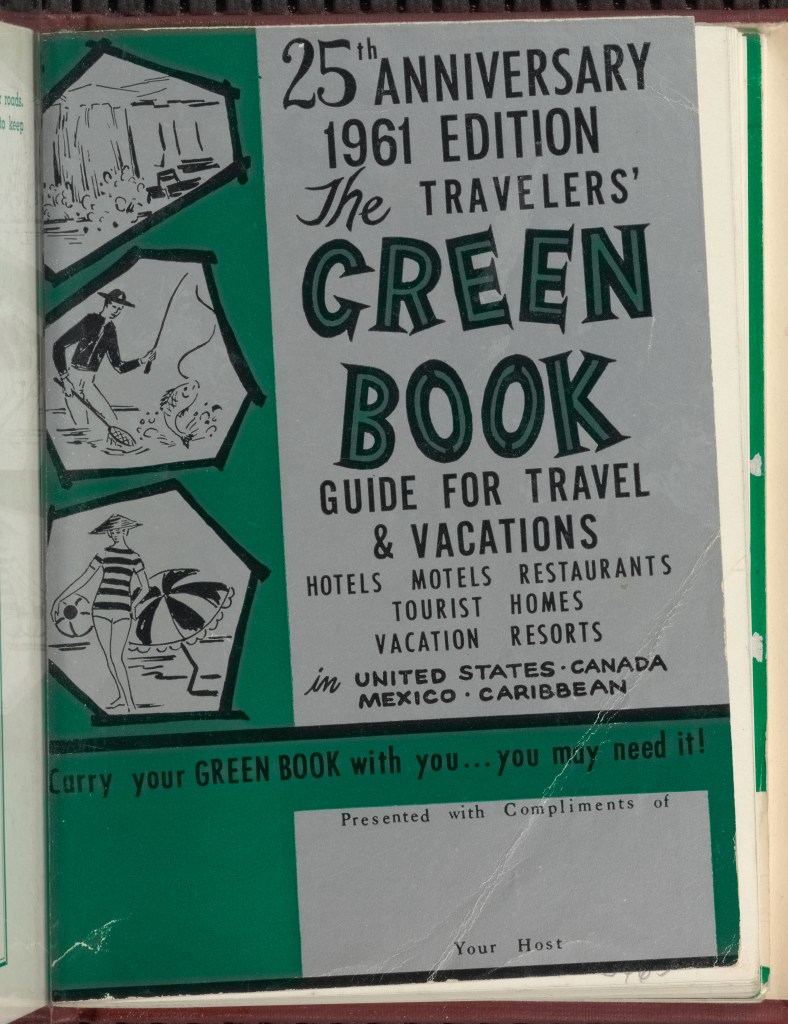

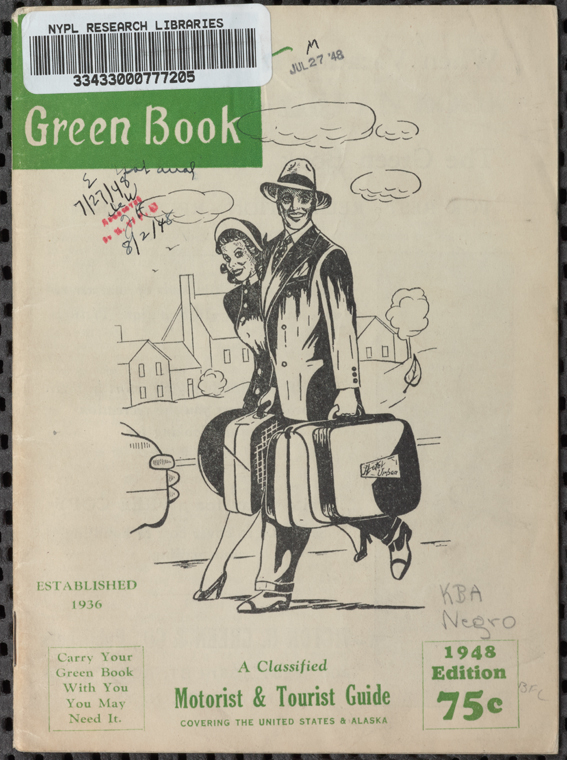

In 1961, The Negro Travelers’ Green Book, known simply as the Green Book, had been helping African Americans navigate both America’s landscape and its structural racism for 25 years. Prohibited from patronizing “white-only” establishments like hotels, restaurants and gas stations, and even confronted with entire towns where blacks were told in explicit terms to leave before sundown, black travelers used the Green Book to traverse the United States in relative safety and comfort. In just a few years, The Civil Rights Act of 1964 would make segregation illegal and render the Green Book unnecessary, but until then it was essential, with a circulation of two million by 1962.

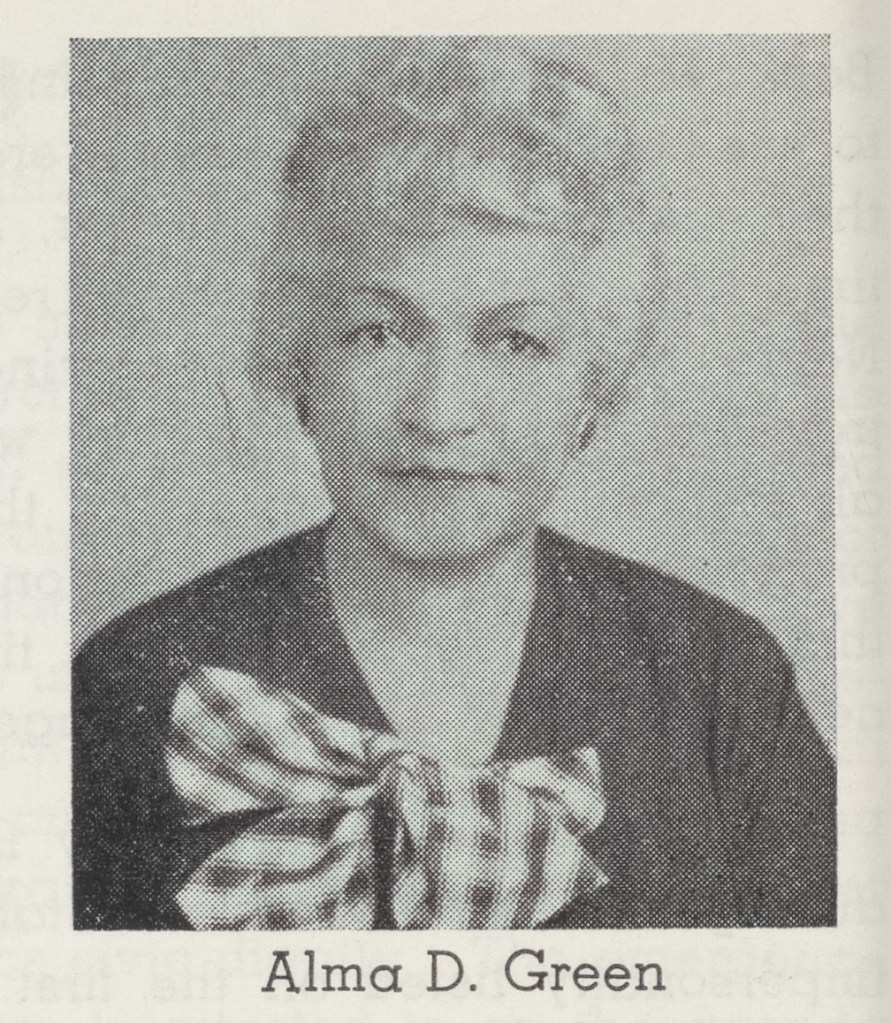

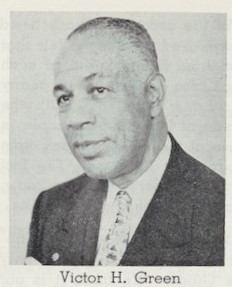

At the helm of the Green Book during its apogee was Alma Duke Green, whose life had begun in the American South around the same time as the enactment of the Jim Crow laws which had made the Green Book necessary in the first place. The widow of Victor Hugo Green, an African-American postman who began publishing the Green Book in Harlem, New York, in 1936, Alma looks elegant and serene in the photo of her that appeared in the 1961 Green Book, alongside an all-female editorial staff. She seems to defy both age and any sign of all she had been through and overcome. Described by the Green Book’s assistant editor as “attractive and astute,” Alma was a true steel magnolia who had lived in and through some of the most culturally- and historically-important places and events of late-19th and early-20th century African-American history.

Though officially editor for only a few years, Alma played a significant role in the creation and evolution of the Green Book, an important part of American history that has only recently begun to be explored. Among the work on the subject is The Green Book Chronicles, a film-in-progress by Calvin Alexander Ramsey and Becky Wible Searles, who have noted that Alma “appears to have actively supported and been involved in this venture from the start, eventually taking over as editor when Victor stepped away from that role.” Beyond that, however, little has been written about the mother of the Green Book.

Racism and Renaissance

Alma died in March 1978, a few months shy of her 89th birthday, having witnessed the birth and passing of both the Jim Crow era of legalized racial segregation and discrimination, and the Great Migration of some six million black Americans away from the southern United States. Her life had been intimately tied to and impacted by both, and though most of the credit for the Green Book has gone to Victor, without Alma and her experiences, the Green Book might never have existed.

Like Victor, who passed away in 1960, Alma died in Harlem, where she lived for nearly 50 years. The Greens had moved there around 1929 from Hackensack, New Jersey, where Victor had his postal route. They arrived just in time to experience the waning years of the Harlem Renaissance, a period of artistic and intellectual brilliance acknowledged by the Smithsonian as “one of the most significant eras of cultural expression in the nation’s history.” Although the Greens had no children, the Green Book – originally titled The Negro Motorist Green Book – was conceived in their apartment in Harlem around 1932 when, according to the 1956 edition, “…not only [Victor Green] but several friends and acquaintances complained of the difficulties encountered; oftentimes painful embarrassments suffered which ruined a vacation or business trip.”

In 1936, the year the first issue of the Green Book was published, one of the Harlem Renaissance’s most illustrious figures, W.E.B. Du Bois had just returned from a visit to Nazi Germany. There, he wrote, despite the terrible policies of the Nazis, “a black man… would not be insulted nor guyed [ridiculed]; nor, least of all, would he be refused such accommodation or courtesy as he demanded,” as he (or she) would in the United States.

A good part of Alma’s and Victor’s first-hand knowledge of such treatment would have derived from their travels between North and South to visit Alma’s friends and family in Richmond, Virginia. On the journey, they undoubtedly encountered their fair share of what the introduction to the 1948 Green Book euphemistically described as “difficulties and embarrassments,” but which always involved either the threat or reality of violence. At the very least, black travelers like the Greens would have had to prepare for the inevitability that there would be no place for them to stop for even the most basic needs and services. Social historian Candacy Taylor, whose book, The Overground Railroad: The Green Book and the Roots of Black Travel in America, will be published fall 2019, explains that, “To avoid the humiliation of being turned away, they often traveled with portable toilets, bedding, gas cans, and ice coolers.”

Alma’s personal experiences with Jim Crow and the hazards of travel went even deeper, however. Whereas Victor was born in New York and had lived nearly all his life in either New York or New Jersey, Alma was born in Richmond on June 9, 1889. She was an early participant in the Great Migration, joining approximately 1.6 million African Americans in the first wave of the movement, which lasted from 1910 to 1940. As a result of these experiences, Alma knew fully and personally how the Jim Crow laws of the American South affected those who lived under their yoke, as well as what traveling to and from the North entailed in the early 1900s.

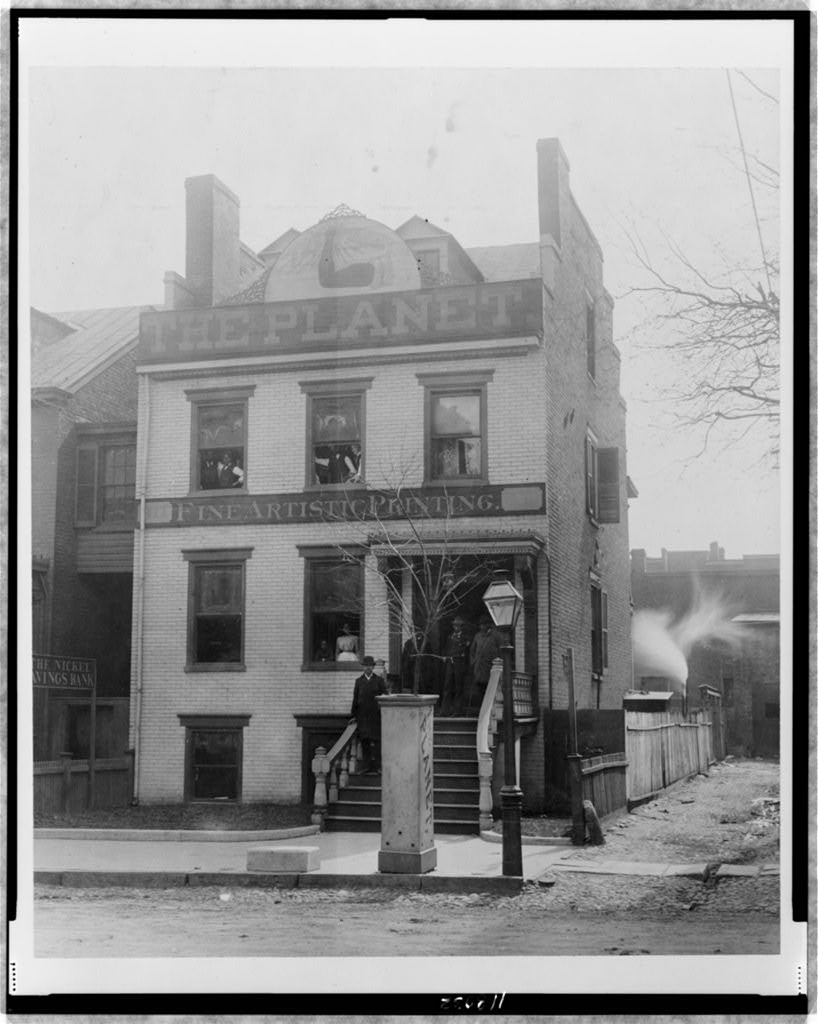

The flip side of her early experiences was that she had the advantage of experiencing first-hand how rich and brilliant African Americans and their culture could be, long before she ever stepped foot in Harlem. Alma was born and raised in Richmond’s Jackson Ward, recognized – in the words of the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, as “one of the most significant black neighborhoods in the United States in the 19th and early 20th centuries.” There, Alma lived among black activists and entrepreneurs like John Mitchell, Jr., editor of the African-American newspaper the Richmond Planet, and Maggie Lena Walker, the first woman bank president of any race in the United States. Jackson Ward was both a reaction to and a refuge from endemic segregation, structural racism, and poverty.

As fortunate as she was to live in a culturally-rich community with inspirational black men and women all around her, life would not have been easy. The middle of three surviving children, Alma and her brothers appear to have had a relatively stable early life that was suddenly and inexplicably disrupted. Alma’s father, William James Duke, worked mainly as a plasterer, and it’s possible her mother was a homemaker. For a time, Alma seemed primed to follow in the footsteps of Maggie Lena Walker. Like Walker, she attended Richmond’s Navy Hill School, considered one of the best primary schools for the city’s black children, followed by high school, most likely at another Walker alma mater, the Richmond Colored and Normal School. By contrast, Victor, who spent his childhood in New Jersey, only received a seventh-grade education.

Somewhere around the mid-to late-1890s, what little stability the Duke family had seems to have disintegrated. The fate of Alma’s mother – identified in later documents both as Nannie Terrell and Nannie Spotswood Terry – is unclear, but it’s possible she died around this time. Simultaneously, Alma’s father disappeared from public records like the city directory and 1900 federal census until 1902. As for Alma, her elder brother William Jr., and younger brother Robert, all three were recorded as living with relatives in the 1900 census. Alma, living in a different household than her brothers, managed to continue her education during this period, though she ultimately did not graduate from high school.

Thrust into a workforce that offered few options for black women, Alma was working as a dressmaker by 1907, when she was 18. In 1910, she was as a live-in servant for the family of a Richmond, Virginia, tobacco merchant named William H. Morton. By 1913, she was listed as a seamstress in the Richmond city directory but was also spending at least part of the year in the New York and New Jersey area. One of the bright spots of Alma’s early historical record comes from this period. On June 11, 1913, Hackensack’s The Evening Record reported: “…a surprise party was tendered Miss Alma Duke by a number of her friends at the residence of Mr. and Mrs. Wm. Watson on Berry street. A most enjoyable evening was spent.”

Lost and Found

At some point over the next two years, Alma left Richmond behind for good, living first in New York, then in the Watson home on Berry Street in Hackensack. Although she may have settled permanently in New York before 1915, the final move may have occurred only after the tragic death in Richmond of 27-year-old William Jr. of tuberculosis meningitis on October 31, 1915. He had been ill for at least 10 months before his death. It may have been the final straw for the family, as statistics from the time reveal how racial inequities meant that black Virginians were three times more likely than whites to die of tuberculosis.

After William Jr.’s death, Alma, her father and surviving brother remained residents of either New York or New Jersey for the rest of their lives. William Sr. and Robert remained in New York, while Alma eventually settled in Hackensack. There, judging by the social pages of The New York Age, an African-American newspaper, she was actively involved in the local African-American community. Also participating in many of the social activities was Victor Hugo Green, whose family had moved from Harlem to Hackensack when he was young.

On Sept. 8, 1917, Alma and Victor obtained a marriage license in Brooklyn, New York, marrying sometime after that. A few months earlier, Victor had completed his mandatory registration for the World War I military draft, and on June 20, 1918, he left his new bride behind when he shipped out as a supply sergeant in the U.S. Army. After his return, the couple settled again in New Jersey, first in Little Ferry and then in Hackensack, both in New Jersey’s Bergen County. Victor returned to working for the U.S. Postal Service, while Alma appears to have worked as a homemaker.

Hackensack was not a Jackson Ward or Harlem, but it was neither an intellectual and political backwater nor devoid of a vibrant African-American community. The WPA Guide to 1930s New Jersey, though written in the decade after the Greens moved to Harlem, noted that, “Many of the 2,530 Negroes [living in so-called negro section of Hackensack] are active in the movement to better their economic position through political action, and have won recognition to the extent of three Negro appointments to the local police force.”

Family was important to the couple. In New Jersey, the Greens lived near Victor’s parents and siblings. Victor’s brother William was editor of the Green Book for several years before his untimely death in 1945. Following their move to Harlem, first William Sr., then Robert Duke came to live with Alma and Victor in their apartment at 938 St. Nicholas Avenue. Robert had worked as a chauffeur in New York City, so his experiences also likely contributed to the content of the Green Book.

Victor worked for the Post Office, delivering mail in New Jersey, until 1952, when he retired after 39 years. In his retirement, he gradually reduced his workload on the Green Book, passing more responsibility to Alma and a growing staff. In 1959, Alma was finally given official recognition when she was put on the masthead as editor. Following a short illness, Victor died on October 16, 1960, after the 1961 issue of the Green Book had already been published. Most of those who purchased the Green Book that year would have had no idea of his passing unless they happened to read his obituary in a newspaper like the New York Amsterdam News, which had a predominantly black readership.

The 1966 issue of the Green Book was the last. Alma had lived to see the day which had long been anticipated in the pages of the publication. For many years, beginning with the 1948 issue, the introduction to the Green Book had included the following statement: “There will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published. That is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges in the United States. It will be a great day for us to suspend this publication…”.

Though always credited to Victor, the statement could just as well have been penned by Alma. But a tradition once established is difficult to alter. In the age in which Alma lived, African American women’s voices and experiences were suppressed by the double burden of racism and sexism. Alma’s role in the Green Book was never outlined or highlighted, establishing the tradition that it was trivial. She passed from the world in 1978 without any recognition of her or her contributions to the millions of African Americans who managed to stay a little safer on the roads thanks to the Green Book.

***

Postscript: I first read about Alma Duke Green in Jan Whitaker’s Restaurant-ing Through History blog about “Green Book Restaurants,” and was immediately interested to know more about her. What I found in investigating her further was that she was never given more than a line or two in any of the histories of the Green Book. Using archival records and primary source material previously unearthed, I have tried to begin to trace Alma Duke Green’s life and her contributions to the Green Book in order to place her in the history she helped to create. I hope others will continue to build on this effort.

Victoria, brilliant addition!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Jan.

LikeLiked by 1 person

An excellent and very timely essay. The movie may have been panned by critics, but at the very least it draws attention to a painful part of our history, and does so in a way that makes it understandable to younger audiences who may have only an abstract idea of segregation. (I liked the film, and felt that some of the criticism missed the point.) Your essay adds important information to the story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks for the thoughtful comment. I haven’t seen the film, but at the very least – and to your point – it has drawn attention to the history of segregation and the Green Book.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great to see this, Tori! Such extensive research that ties many loose ends together. Thank you for mentioning our film “The Green Book Chronicles”! Looking forward to staying in touch 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Becky! I am so glad to help bring her to light, and I’m grateful to know you.

LikeLike

[…] The movie “Green Book” has brought attention to Victor Hugo Green, the African American postman who began publishing the guide to places that welcomed African American travelers during the Jim Crow era. Victoria Martinez writes about his wife, Alma Duke Green, who contributed to the publication and continued it after the death of her husband. Read the article by clicking here. […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello, I live in Jackson Ward and know many of the original families. I love this! Thank you

LikeLiked by 1 person

How wonderful! Thank you!

LikeLike