By Victoria Martínez

One of the key premises of this blog is to contribute to filling the yawning gaps in the representation of women in history. Women are, of course, represented in narratives of the past. However, their representation is still frequently limited; for example, to their roles in relation to male figures in history. Other patterns of representation do women a disservice, such as the overrepresentation of a few women at the expense of others.1 This situation is complicated when the women in question are also artists. This is no better summarized than in the following statement by artist Poppy Collier-Doyle:

Throughout the history of art, women have been painted and idolised. However, there has been little representation of women behind the canvas, despite their contributions to the visual arts world.2

Needless to say, women have typically led the crusade to bring attention to female artists – both historical and contemporary.3 Although I am not an art historian, I am a historian who specializes in women’s history and also greatly appreciates art (something for which I have zero personal talent). For these reasons, I enthusiastically took the opportunity to write about Polish artist Jadwiga Simon-Pietkiwicz (1909-1955), after finding a program for an exhibition of her art in Sweden in June 1945, just one month after she arrived in the country as a liberated prisoner of the Ravensbrück concentration camp.4

Both the artist and her art are extraordinary. As a prisoner in Ravensbrück, she had risked death to draw and paint her fellow prisoners in the hope that the paintings, if not the people she painted, would survive to show the world what these women suffered at the hands of the Nazis. The risks she ran were not simply in the painting and drawing but also in “stealing” the necessary supplies needed to create these works of art and in effectively hiding them from her captors. Some of the artworks were smuggled out before her liberation while others were carefully concealed in her clothing on her arrival to Sweden.

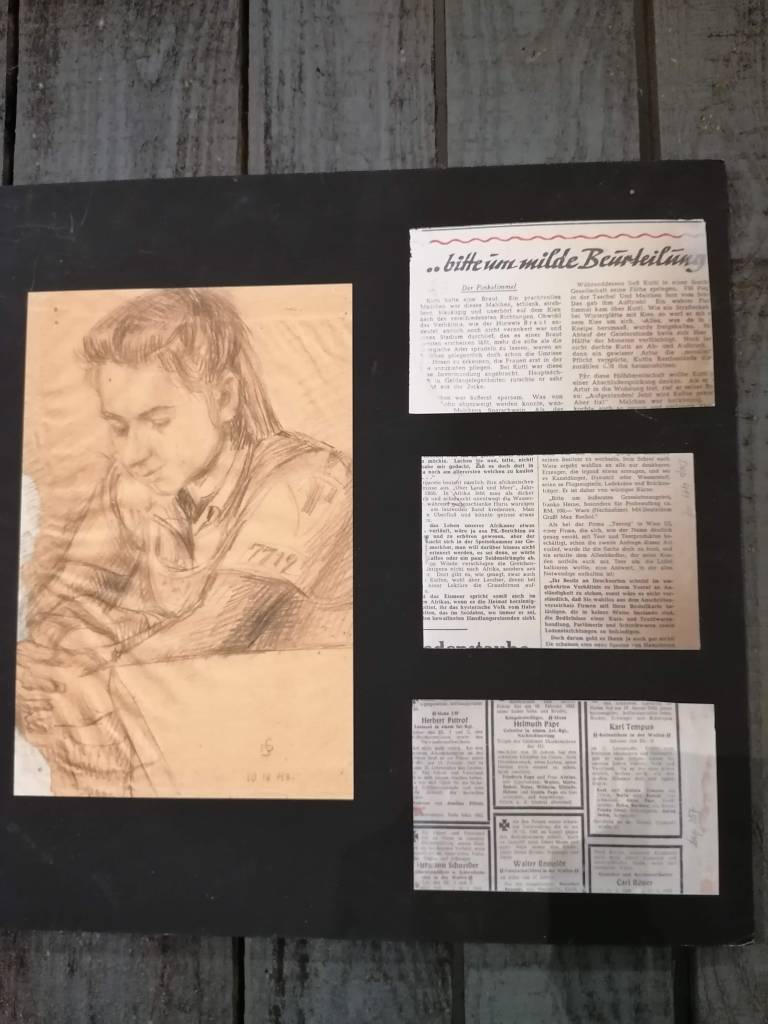

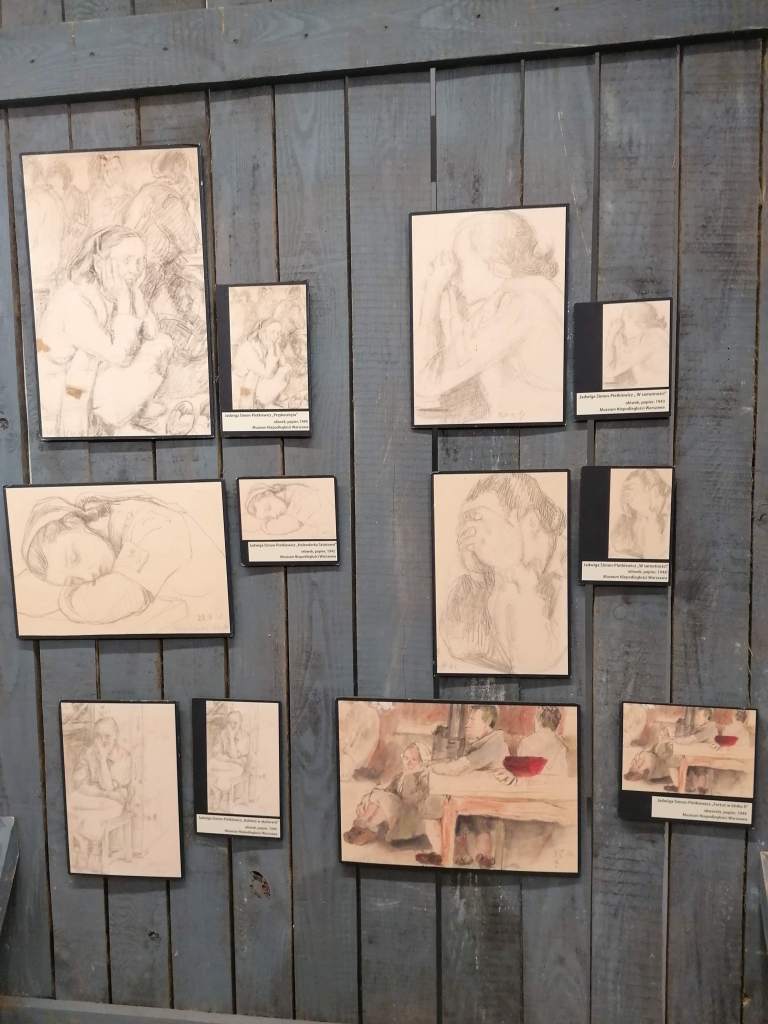

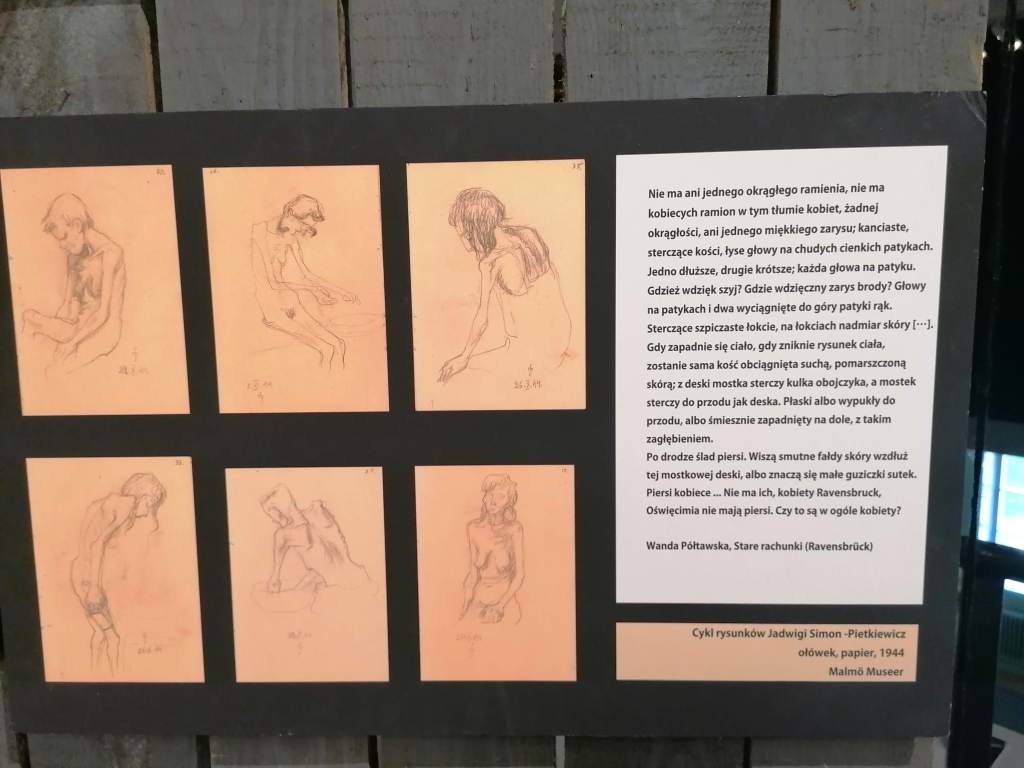

(Click for image captions and credits)

Left: A drawing by Jadwiga Simon-Pietkiewicz, dated November 3, 1944, titled Madame Bergeret One Hour before Her Death. From the collection of Moderna Museet, Stockholm, Sweden. Reprinted with permission. Center: Drawing from one of Jadwiga Simon-Pietkiewicz’s Ravensbrück sketchbooks, which may have been displayed in the Lund exhibition. Creative Commons image from the collection of Malmö Museer, Sweden. Reprinted with permission. Right: Watercolor titled Hungarian Jewish Woman “Chinese” by Jadwiga Simon-Pietkiewicz, dated February 18, 1945. Copyright Jadwiga Simon Pietkiewicz, photographed by Matilda Thulin, Malmö Konstmuseum (Stockholm, Sweden). Reprinted with permission.

My study focused on the reception of Jadwiga’s art in Sweden, which had been nominally neutral during the Second World War and therefore had not witnessed the carnage firsthand. Going against the grain of the representation of women’s art, Zygmunt Łakociński, a Polish émigré academic, initially arranged for Jadwiga’s art to be displayed in Lund, Sweden, along with Swedish art critic Greta Åkerlund. After the success of the initial exhibition in Lund, her artworks and those of two other Polish survivor artists were displayed in galleries around Sweden and in Copenhagen, Denmark in 1945 and 1946. Many of Jadwiga’s works of art were sold, including to Swedish art museums and members of the Swedish royal family. As I have argued, the exhibition of the artworks – which displayed raw suffering and death – enabled the Swedish public to witness the Holocaust in a way that photography of human suffering had failed to do.5

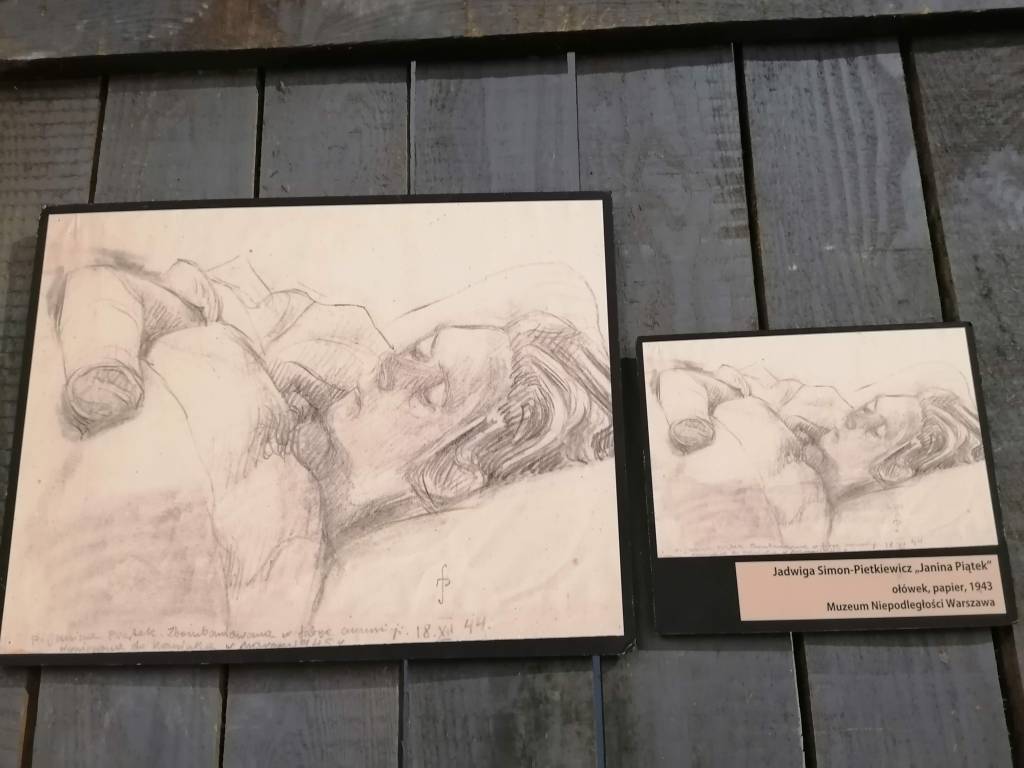

One of the aspects that drew me to Jadwiga’s art in the first place was how she represented women and their suffering in art. As I researched and wrote about her, I was also inspired by the excellent work being done by other women to represent her, her art, and the suffering and experiences of the women she drew and painted. Among these was Polish art historian Agata Pietrasik, whose 2021 book Art in a Disrupted World: Poland 1939–1949 provides a fascinating and accessible look at how art served as a way of maintaining humanity during and after the Second World War and the Holocaust. Another was Polish historian Barbara Czarnecka, of the University of Białystok in Poland, whose scholarship provides important insight into the woman behind the art. Most recently, Czarnecka created a traveling exhibition of artwork primarily by Jadwiga Simon-Pietkiewicz, which I had the pleasure to see on a recent visit to the Swedish cultural museum, Kulturen in Lund. Czarnecka and historian Barbara Törnquist-Plewa of Lund University in Sweden (who I was lucky enough to have on the examination committee for my Ph.D. defense), have co-authored a book about Jadwiga Simon-Pietkiewicz, which should be published later in 2024.

(Click for caption and credits)

Personal photos taken at the exhibition, “Women’s Concentration Camp Experience” at Kulturen in Lund, May 2024. All rights reserved.

It is encouraging and exciting to see so much excellent work being done on Jadwiga and her art. Her art represents women not as objects of desire but as human beings who suffered because of a senseless racial idealogy. In their own way, they are beautiful. As I argued in my article, the “beauty” in these depictions of the women in Ravensbrück is an intangible quality that has the power to draw viewers into a moral relationship with the suffering of others.6 But this is only possible if these artworks are seen. The work scholars are doing now is thus important not only in terms of filling gaps in the representation of women artists but also in facilitating the bond that her art can create between viewers and the suffering of women in the past.

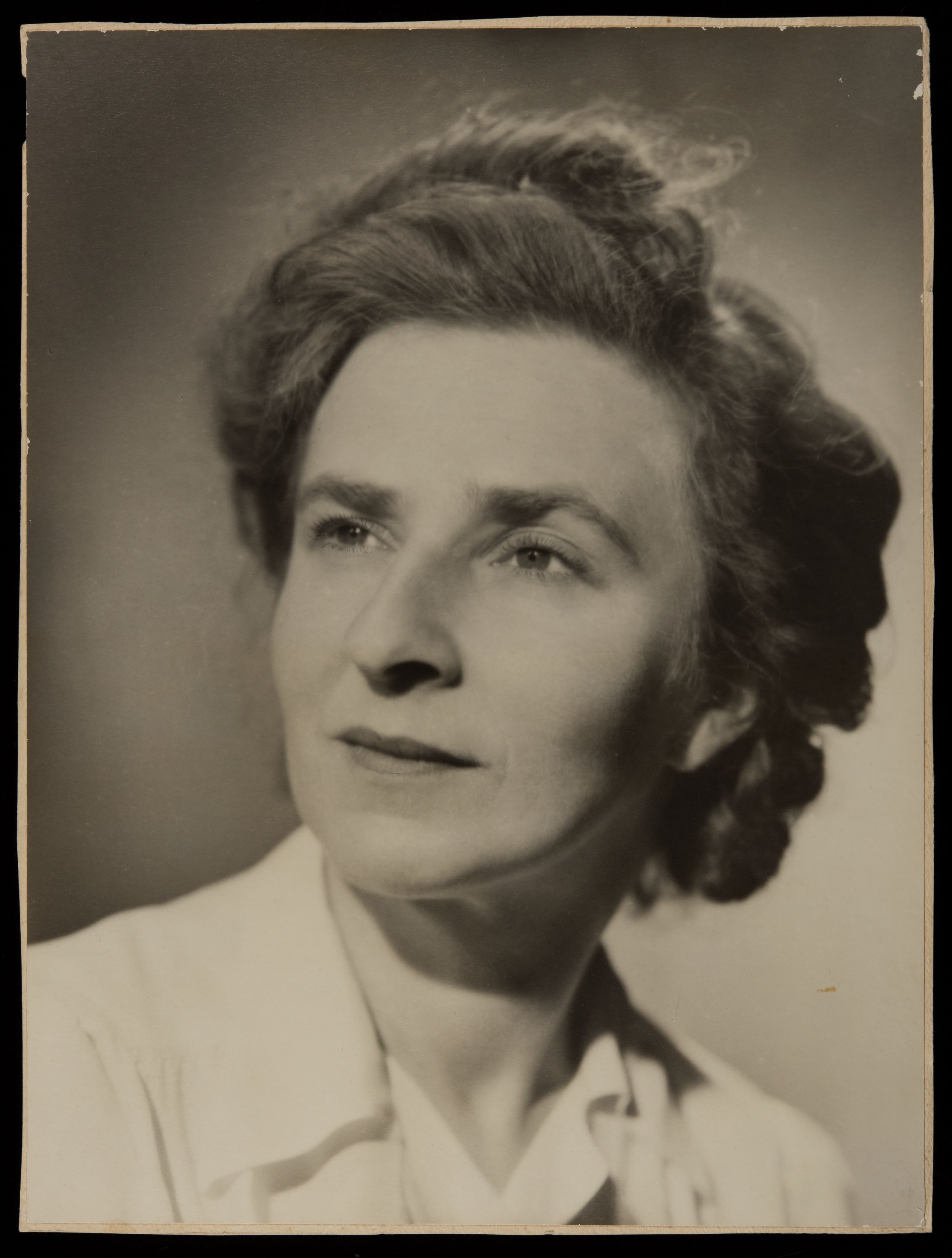

Featured image: Jadwiga Simon-Pietkiewicz’s drawing of Janina Piątek, dated November 27, 1944. Janina was murdered in the gas chamber in March 1945. Public domain image courtesy of The Polish Research Institute collection, Lund University Library, Sweden.

- See, for example: “Where are the Women?” National Women’s History Museum, https://www.womenshistory.org/social-studies-standards, accessed August 10, 2024, Perez, Rachel Lee, “‘A Womanless History’: The Importance of Including Women in the Historial Narrative,” Ms., August 25, 2022, https://msmagazine.com/2022/08/25/women-history-textbooks/, accessed August 10, 2024. ↩︎

- Collier-Doyle, Poppy. “The representation of women in art throughout history,” https://www.poppycd.art/the-representation-of-women-in-art-throughout-history/, accessed August 10, 2024. See also: National Museum of Women in the Arts, https://nmwa.org/support/advocacy/get-facts/; “What does it mean to be a woman in art?” Tate, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/women-in-art, accessed August 10, 2024. ↩︎

- For example, the “Guerilla Girls” of the 1980s: https://awarewomenartists.com/artiste/guerrilla-girls/, accessed August 10, 2024. ↩︎

- Martínez, Victoria Van Orden, “Witnessing the Suffering of Others in Watercolor and Pencil: Jadwiga Simon-Pietkiewicz’s Holocaust Art Exhibited in Sweden, 1945-46,” Holocaust and Genocide Studies, 37, 2 (2023), https://academic.oup.com/hgs/article/37/2/273/7445654. ↩︎

- ibid ↩︎

- My argument is based on the theories of scholars Brett Ashley Kaplan and Melissa Raphael. See Martínez 2023. ↩︎