By Victoria Martínez

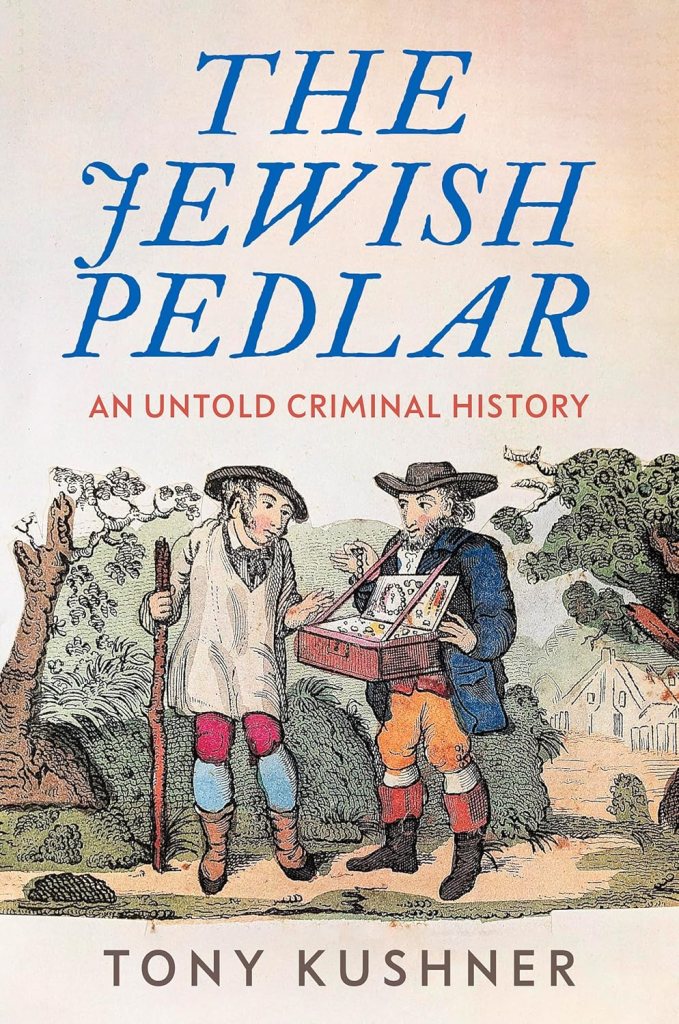

The story of Jacob Harris brutally murdering an inkeeper, his wife, and their maid in Ditchling, a village in East Sussex, England, in 1734, has been told and retold many times. So has the story of Harris’ hanging and gibbeting – the public display of a criminal’s decomposing corpse in a suspended iron cage as a deterrent to would-be criminals. Not that you’ve probably ever heard of either. Even if you had, the story was almost certainly twisted and distorted beyond any semblance of reality. And this is precisely why Tony Kusner’s latest book, The Jewish Pedlar: An Untold Criminal History (Manchester University Press, 2025), is not only relevant and necessary but also fascinating. Because the crimes, the criminal, and the punishment have only ever been told as frequently inaccurate stories and never as part of history, with all that this entails.

In researching and writing The Jewish Pedlar, Kushner had to be part historian, part murder detective to unravel not only the facts of the triple murders perpetrated by Jacob Harris in 1734, but also to situate Harris and the murders at the intersection of criminal history, Jewish life, peddling, folklore, and antisemitism in early modern and modern England. Although the murders and punishment of Jacob Harris were a local sensation covered in newspaper reportage at the time, many facts were omitted, not least about Harris himself. Beyond the brutality of the murders and punishment, one detail that made its way into the stories of the murders was that Harris was Jewish.

At the time of the murders, it had been less than eighty years since Jews were readmitted to England following their expulsion in the late thirteenth century. To be Jewish in England during this period was to live both in and outside of the mainstream of society, legally and socially. For Harris, this liminal state appears to have been exacerbated by his connection to and participation in smuggling – an activity that may have connected him with one of his victims, innkeeper Richard Miles. At the time, however, relatively little was made of Harris as a Jew. And, aside from sparse official records, ballads, personal diaries, and local oral histories, few contemporary sources produced reliable information about Harris and the murders he committed and little was written about the murders for more than a century.

It wasn’t until the mid-nineteenth century that Victorian antiquarians began to call Jacob Harris a “Jew pedlar,” effectively conflating Judaism and criminality (via the murders and suspected smuggling activities associated with them) by invoking one of the few means of subsistence available to Jews in England and elsewhere during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Kushner stops short of calling this antisemitism, instead writing:

It would be crude to suggest that their construction of Harris was purely the result of Christian anti-Judaism, but equally naive to argue that it did not influence their connection of his crime to inherent Jewish traits. (Kushner, p. 158)

Either way, Harris’ murder of Richard Miles, his wife, and their maid became (more than a century after the fact) a distinctly Jewish crime, rather than just a crime allegedly connected to smuggling.

The history Kushner relates in The Jewish Pedlar does not end here, which is why it is worth a full read. Why this history – and all of the stories behind it – matters now must be left to the discernment of the reader.