By Victoria Martínez

“Craftivism” may be a recent term, but it is far from a new concept. Craftwork and activism have a long history, and I recently had the opportunity to give a lecture to the Crewel Work Society about one of history’s intriguing and inspiring craftivists: Rachel Kay-Shuttleworth (1886-1967). I’ve adapted the lecture for the blog to continue to share her fascinating story.

An Inspiring Childhood

Born in the north of England in 1886 into a life of wealth and privilege, Rachel Kay-Shuttleworth, like most young women of means, was taught to embroider from a young age, and this avocation became her passion in life. More than that, she came to understand embroidery as a form of creative expression that had the power to improve individuals and society. Rachel’s birthplace, Gawthorpe Hall – pictured here in 1884 (Figure 1), two years before Rachel’s birth – is located between Padiham and Burnley near the Pennines in northeast Lancashire. The foundation stone of Gawthorpe Hall was laid in August 1600, late in the reign of Queen Elizabeth I of England and Ireland, who died in 1603, the year Gawthorpe was ready to be occupied. The structure you see in this image was built around an early fourteenth-century peel tower that was built as a lookout for invading Scots.

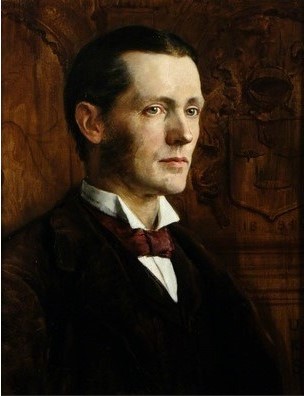

In 1388, Ughtred de Shuttleworth acquired 25.5 acres of land on the banks of the River Calder, including the land surrounding the tower. Within six generations, Ughtred’s descendant, Sir Richard Shuttleworth, was a wealthy and successful London barrister who had been made a Serjeant-at-Law – an English barrister of the highest rank – in 1584 and Chief Justice of Chester in 1589. The wealth and landholdings of the Shuttleworth family had increased so much that they were asked to lend money to Queen Elizabeth I in 1588 and 1597. The construction of Gawthorpe Hall solidified the Gawthorpe family’s status as landed gentry in Lancashire. Rachel’s father, Ughtred James Kay-Shuttleworth (Figure 3), was named for his esteemed ancestor. This naming was significant because the Shuttleworth name had nearly died out in the previous generation, when the Gawthorpe Shuttleworths were left with only a female heir, Janet Shuttleworth. In 1842, Janet married Dr. James Phillips Kay, who changed his surname to Kay-Shuttleworth.

In 1871, Ughtred married Blanche Marion Parish (Figure 2), the daughter of diplomat Sir Woodbine Parish. The couple had their first child in 1872 and eventually had a total of six children. In addition to continuing the family line of Gawthorpe Shuttleworths, Sir Ughtred and Lady Blanche Kay-Shuttleworth upheld the life of Gawthorpe Hall as the seat of a family that was important both nationally and locally. Sir Ughtred also held important political positions in the British government, including serving as a Privy Councillor to Queen Victoria.

Rachel, pictured here at the age of five (Figure 4), was the third child and daughter born to Ughtred and Blanche. Considering the recent concerns about continuing the family line, the Kay-Shuttleworths were eager to have a son, which they finally did in 1887, followed by another in 1890. In 1894, their sixth and final child, another daughter, was born.

As with other children of her time and class, Rachel and her siblings were raised by nurses, nannies, and governesses. Rachel’s biographer, Canon G.A. Williams, claims that young Rachel was “not a bright child” but reveals what he regarded as her strengths in this way:

“At an age when most children are content to play with dolls, she was making an intelligent study of the stars to help her navigate the desert or the sea when her ambitions were realized. She took early to the needle and found enjoyment not only in creating things but in the workmanship involved.”1

In contradiction of his early description of Rachel as not “bright,” Canon Williams explains that she had a “phenomenal memory.”2 Until she was 15 and sent to a girls’ boarding school, Rachel spent her youth soaking in the beauty of her home, perhaps using her “phenomenal memory” to take mental pictures of the plethora of designs that surrounded her. Although the exterior of Gawthorpe Hall is late Elizabethan, the interiors exemplify the best of many subsequent periods of architecture and design, from the Jacobean to the Victorian. Below is a picture from around 1910 of the drawing room at Gawthorpe, which was originally the Hall’s dining room (Figure 5). The walls and ceiling are the original Jacobean designs. The ceiling plasterwork took five months to create in 1605, reportedly by Italian craftsmen, and features vines and oak branches.

In the book Backcloth to Gawthorpe, Michael P. Conroy gives the following description of domestic life in this room at Gawthorpe during Rachel’s youth:

“In the evening, the maids and the daughters of the family would gather in the drawing room into which a fire had been put by the footmen, and they would sit around the large table with the lamp in the middle. They sewed red flannel petticoats for the poor…”3

Conroy’s description demonstrates how closely sewing and social work were intertwined for the women at Gawthorpe.

Everywhere you look in Gawthorpe Hall – ceilings, walls, furniture, clocks, tiles, etc. – there is a feast for the eyes of various patterns and designs – most naturalistic – from different periods of time (Figures 6-10).

The room below, the family dining room, was originally the great hall of Gawthorpe Hall, where banquets and performances would have been held in the seventeenth century (Figure 11). The original plasterwork ceiling in this room had to be replaced in the mid-nineteenth century with a modified reproduction of the original (Figure 12). An addition was the family initials, “KS” for Kay-Shuttleworth. I emphasize the ceilings because tradition has it that Rachel’s love of design was particularly inspired by the various patterns and designs on them.

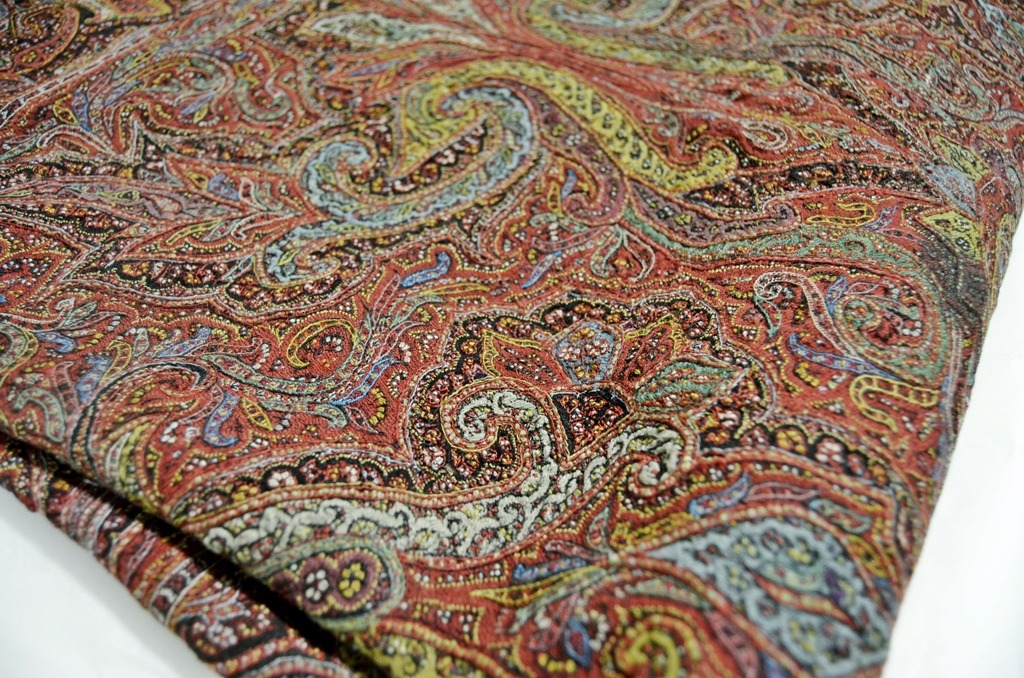

In addition to the house, Rachel was also exposed to beautiful design in the clothes worn by her mother, Blanche, and other women of the time. Among the items in the Gawthorpe Textiles Collection is this “mitten” of black Brussels silk lace from the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century (Figure 13) that was worn along with its mate by Blanche while in mourning, and this cashmere, embroidered shawl (Figure 14) made in India in the late eighteenth century. The Gawthorpe Textiles Collection describes it as an amli shawl, which would typically be made for and worn by Indian royals and nobles. Soon, Rachel began acquiring her own beautiful objects, such as this hand mirror (Figure 15) that was gifted to her by her parents in 1900, a souvenir from a trip they had made to Germany. The wood frame of the mirror is covered in brown leather, which has been embossed on the back with a peacock that was originally painted in bright blue, green, and gold. According to the Gawthorpe Textiles Collection, peacocks were one of Rachel’s favorite motifs.

Rachel led a privileged life at Gawthorpe Hall and the family’s other residences, which were visited by many important and interesting individuals. The first image below (Figure 16) is a photo taken at Gawthorpe Hall in November 1896, when Rachel was ten years old. The man seated is Thomas F. Bayard, who was then United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom. Rachel is the young girl wearing a hat with her face in profile, picture right. The photo underneath (Figure 17) was taken at the family’s country estate in September 1903. Among those pictured are Dr. Arthur Winnington-Ingram, Bishop of London from 1901 to 1939. Perhaps no visit to Gawthorpe was as exciting for the family as that of King George V and Queen Mary in 1913. Rachel is seated in the front row, picture right, again looking away from the camera.

Beauty and Tragedy

Rachel formally entered society when she was 16, early in the reign of King Edward VII. Canon Williams writes of her, “She was enchantingly pretty with her golden hair and blue eyes and she adored dancing.” At the same time, he wrote, she was “serious minded and with no small talk she was bored with anyone who had intellectual or artistic interests, though she forgave them if they danced well enough.”4 The Edwardian period is known as a time of upper-class decadence and even debauchery at the highest levels. But although Rachel moved in the highest circles, she found pleasure not in superficial pleasures but in art and handiwork. Having taken to the needle early, as Canon Williams described,5 Rachel began developing her skill at lacemaking while still in boarding school and was soon teaching the skill to her classmates. She and a friend studied art in Paris, and she gave lectures on art appreciation and history in London. Like many young women of her class and era, she traveled extensively, paying close attention to art and architecture and learning new techniques of lacework and embroidery. Her journeys took her to the United States, Germany, Italy, and North Africa, among others.

On her travels, she was not only learning new techniques but also collecting examples of embroidery and other craftwork. Rachel purchased this early eighteenth-century colifichet embroidery – a rare type of embroidery with the same design on both sides of the fabric – at an antique store in Italy around 1910 (Figure 19). Apparently, it was very dusty and dirty when she purchased it, but her eye was sharp enough to see beneath all that. According to the Lancashire Textile Gallery, “The design would be pricked out and the sewing was often carried out by two people, one on either side, passing the needle back and forth through the pre-pricked holes.”

At home in England, Rachel lived between Gawthorpe Hall, London, and the family’s country estate in Westmoreland. In each location, she left her mark, giving lectures, teaching embroidery and lacemaking, and creating beautiful works of art for herself and others. A striking example is the magnificent bed hanging she created between 1910 and 1918 for a seventeenth-century carved oak tester bed Rachel’s parents bought for her (Figure 20). The crewel work textile is called the “Tree of Life” and was inspired by Jacobean floral motifs and coats of arms like those that adorn Gawthorpe Hall (Figure 21).

Rachel had been strongly influenced not only by Gawthorpe Hall, however, but also by Lancashire, where half of the world’s cotton was produced in the mid-nineteenth century. The industrial revolution was in high gear with all the problems this entailed. As a young woman, before the First World War, one of Rachel’s key concerns was the impact of mechanization on creative expression and its benefits to individuals. According to Canon Williams, Rachel believed that “personality develops through expression and that without opportunity for creative work personality must suffer.” The solution, she felt, was to create opportunities for people to find “satisfaction and stimulation” through craftwork.6

As we’ve seen, Rachel was raised to do social work from a young age. As prominent members of society and the local community, her parents were expected to provide charity and largesse to the less fortunate. But both were truly devoted to good works, and this sense of social responsibility was inherited by Rachel. In 1883, Blanche and another local woman established a “House of Help” in Padiham for young women in “moral danger,” and Rachel later became its patron. When the First World War broke out in 1914, Rachel threw herself into social work that benefited women whose husbands were fighting in the war. The way she went about this work is notable not only for how personally hands-on she was but also for how craftwork was the conduit for helping these women. Canon Williams describes it in this way: “She therefore set about organizing workrooms for them. This entailed finding premises, recruiting helpers, providing materials and teaching crafts.”7

Rachel was also involved in work related to improving conditions related to the high rate of maternal and child mortality, and in 1915, she was appointed County Commissioner for Northeast Lancashire for the recently formed Girl Guides Movement. Tragically, the First World War claimed the lives of Rachel’s two brothers, Captain Lawrence Kay-Shuttleworth and Captain Edward Kay-Shuttleworth, who were killed within months of each other in 1917 (Figure 22). Both left behind wives and children. Canon Williams writes of Rachel during her period of intense social work during the war that she [quote] “never lost sight of the abiding value of art and the creation of beauty in a world that was tempted to regard these matters as irrelevant in war-time.”8

Even after the war and the double tragedy that befell the family, Rachel did not lose this quality. For me, this work exemplifies that perfectly, and it is one of my favorite pieces of Rachel’s incredible talent and craftsmanship. It is a panel of laid work embroidery that Rachel embroidered while recovering from typhoid fever and gave to her parents that year for their golden wedding anniversary (Figure 23). Here again we see the peacock theme she so loved in vibrant color on cloth of gold, further embellished with gold metal threads and iridescent beetle’s wings on the peacocks’ tails. In the Gawthorpe Textiles Collection are notes written by Rachel, who explained in 1965 that when she embroidered this in 1921, there were around 400 shades of silk floss in the Pearsall Stout Floss range that she used, whereas in 1965, there were only around 40, making this brilliant piece, Rachel observed, impossible to reproduce.

A healing art

Rachel’s involvement with the Girl Guides was one of the key areas where her dedication to craftwork as social work can be seen. As I mentioned, she was appointed County Commissioner for Northeast Lancashire of the Girl Guides in 1915, and she held this position for 30 years. Late in her tenure, in 1939, the Birmingham Evening Mail wrote the following, which I read in its entirety to emphasize the influence Rachel and her passion for embroidery as a pedagogical and social had on the Girl Guides in Northeast Lancashire. The title of the article is “Lancashire Embroidered” and it reads as follows:

“Lancashire appears to have carried off most of the honours at the exhibition of the Embroiderers Guild in Grosvenor Street, London. But, of course, the work is all from the north-west section of the Guild which has done so much to raise the standard of the embroidering art. Thanks, also, to inspiring leadership by such a true craftswoman as the Hon Rachel Kay-Shuttleworth. Some of the work Miss Kay-Shuttleworth has inspired reminded one by its delightful use of heraldry of some beautiful examples of embroidery in Edinburgh. In Grosvenor Street is a design for a Lancashire girl guide standard which would charm the heart of any expert at Heralds College. Coal and cotton, the two great industries of Lancashire, are represented, also the Red Rose, and other country devices. In fact, Mrs. Selby, in planning this design for a standard, has given a lead to the girl guides of all other counties. Embroidery is clearly an art which has some accomplished exponents in Lancashire.”9

The group photo below (Figure 24), in which Rachel is pictured third from photo left, is dated to the previous year, 1938, and features the standard mentioned in the article. It was Rachel who had first suggested that each of the Girl Guiding counties, districts, and companies should have a standard. Rachel had also suggested that the Girl Guides’ County Commissioners should embroider a personal standard for Princess Mary, the daughter of King George V and Queen Mary, as a gift for her marriage. The idea was accepted, and Rachel carried the standard at the wedding service of Princess Mary in Westminster Abbey in 1922.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the Gawthorpe estate was the site of Girl Guides rallies and campouts. At the same time, Rachel was still active in other aspects of community and social work. With the First World War, the cotton industry that had thrived in Lancashire for as long as Rachel could remember began to falter. The 1930s saw an overall decline in cotton production in Lancashire, resulting in the closure of hundreds of factories and the loss of many jobs. As always, Rachel’s solution to the problem of unemployment was craftwork. As Canon Williams writes, “Clubs were the answer, clubs in schoolrooms, in chapels, in old army huts, clubs where the unemployed could go and learn a craft, basketwork, leatherwork, carpentry, needlecraft, woolcraft, fine arts, anything so long as it provided an outlet for personality and an incentive to express and create.”10 Of course, these activities also kept the unemployed from sinking into depression and despair and trained them for other types of employment, which benefited the individuals and society.

creating a collection and a legacy

Rachel retired from her position with the Girl Guides in 1947, at the age of 61, and increasingly spent her time embroidering, teaching, and building her textiles collection. According to the Gawthorpe Textiles Collection, she assembled the collection mainly through donations from family, friends, and acquaintances, as well as – of course – items she had collected and made herself. Her idea was not to keep the pieces in the collection behind glass but rather for them to be “held, touched, and used for educational purposes.” Rachel knew these items would have a life beyond her own and desired that they continue to serve society through the beauty of art and creative expression.

Rachel passed away at Gawthorpe Hall on April 20, 1967, aged 81. She was the last of the Shuttleworths to live at Gawthorpe Hall. During her life, negotiations had been underway to transfer ownership of Gawthorpe from the Kay-Shuttleworth to the National Trust. The negotiations also involved the establishment of a craft hall at Gawthorpe Hall for the display and teaching of craftwork – a long-term dream of Rachael’s – and to this end, she established the Gawthorpe Foundation in the early 1960s. Both ambitions were realized after Rachel’s death.

It is fitting that the collection that Rachel amassed – estimated at around 10,000 to 12,000 items at the time of her death – inspired in part by the beauty of Gawthorpe Hall itself, was preserved. Since her death, the collection has increased by at least three times its original size. Rachel’s legacy of craftwork as social work continues to be honored through the Gawthorpe Textiles Collection, as well as by those who continue to recognize the power of creative expression.

- Williams, Canon G.A. Rachel Kay-Shuttleworth, A Memoir. Kendal: Titus Wilson and Son, 1968, p. 3. ↩︎

- ibid ↩︎

- Conroy, Michael P. Backcloth to Gawthorpe. Lords of Burnley Ltd., 1996 [1971], p. 72. ↩︎

- Williams, p. 6. ↩︎

- ibid, p. 3. ↩︎

- ibid, p. 7. ↩︎

- ibid, p. 9. ↩︎

- ibid, p. 11. ↩︎

- “Lancashire Embroidered.” Birmingham Evening Mail (Birmingham, West Midlands, England). Jun 16, 1939, p. 14. ↩︎

- Williams, p. 17. ↩︎