A major New York City airport is named in honor of her brother, but Gemma La Guardia Gluck’s story of surviving Ravensbrück concentration camp as the political prisoner of Adolf Eichmann unjustly exists in the shadows of history.

By Victoria Martínez

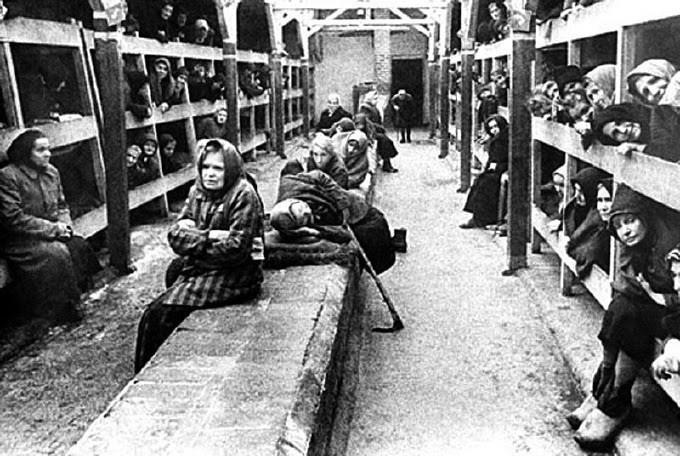

Details of Gemma La Guardia Gluck’s arrest and imprisonment in Ravensbrück women’s concentration camp were part of the testimony at the 1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann, who had been responsible for implementing the Nazi “Final Solution” of Jewish extermination. She had been one of the few – perhaps the only – native-born American women to become a prisoner in a Nazi concentration camp. Despite being in her early 60s, she not only survived the terrible ordeal, but became a beloved “Mutti” (mother, in German) to the women imprisoned alongside her.

In 1961, Samuel L. Shneiderman, a journalist covering the Eichmann trial, discovered that this remarkable woman, all but forgotten and presumed dead, was living in low-income housing in Queens, New York. When he visited her there, he learned that she had hand-written a memoir of her life and experiences not long after her liberation. Recognizing the value of this rare first-hand account of an American woman’s experience in a Nazi concentration camp, Shneiderman edited the manuscript and brought it to publication in late 1961 as My Story. The timing couldn’t have been luckier.

In 1961, Samuel L. Shneiderman, a journalist covering the Eichmann trial, discovered that this remarkable woman, all but forgotten and presumed dead, was living in low-income housing in Queens, New York. When he visited her there, he learned that she had hand-written a memoir of her life and experiences not long after her liberation. Recognizing the value of this rare first-hand account of an American woman’s experience in a Nazi concentration camp, Shneiderman edited the manuscript and brought it to publication in late 1961 as My Story. The timing couldn’t have been luckier.

Though Gemma lived long enough to see the publication of this work, which she had written to “describe all these horrors for the whole world to know how these women had suffered”[1], and to know that Eichmann had been executed in May 1962, she died on November 1, 1962, at Elmhurst Hospital in Queens, just three miles from the airport named after her late brother, New York City Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia[2].

Mothers and Children

In the nick of time, Gemma La Guardia Gluck’s story had been gifted to the world. She wrote of both the horrors she and others experienced and whatever goodness she found with insight and sensitivity.

“There were many mothers with children in Ravensbrück. The little ones, of whom at one time there were perhaps five hundred, added a note of special horror and tragedy to the atmosphere of the camp. They looked like little skeletons wearing rags. Some had no hair on their heads. Nevertheless, they behaved like children, running around and begging things from their elders. They even played games. A popular one was Appell, modeled on the camp’s daily roll calls.”[3]

She dispensed sage advice; the wisdom of a woman who had loved and lost much, including her husband, Herman Gluck, who had been beaten to death over the course of several weeks at Mauthausen concentration camp.

“My advice to young girls is not to choose a husband for good looks. My husband was not at all handsome, but it is the character, the intelligence, diligence, and goodness of a man with which one should fall in love. This was true in my case. I wish that every girl could marry as well and live as happily as I did during thirty-six years of married life.”[4]

In the increasingly overcrowded concentration camp, Gemma had taken it upon herself to help unite and support those around her. While the Nazis actively stoked animosities between the women of different nationalities, religions and ethnicities in Ravensbrück, Gemma worked to bring them together at the dinner table for which she was responsible.

“I had thirty-four women of twelve different nationalities and of several religions at my table,” she explained. “Sometimes the debates waxed hot, and it was exciting to hear the different opinions when they discussed politics. Then I had to become a peacemaker. I had Russians, Czechs, Poles, Norwegians, Yugoslavs, Italians, French, and Hungarians. Many of them could speak two of these languages.”[5]

Gemma also continued her pre-war occupation of teaching English. Both she and her students risked severe punishment for this activity, but Gemma called teaching English to the prisoners “the most gratifying hours I spent in Ravensbrück.”[6]

She called these women “my children”, and they returned the compliment by calling her “Mutti” (mother). The love and respect they felt for her was exemplified by a small “album” they created for her as a gift in Christmas 1944. Filled with personal written messages that would probably have guaranteed all their deaths if discovered, it was a precious memento that Gemma apparently managed to preserve.

“I discovered that true comradeship can develop among those subjected to such conditions,” Gemma wrote. “In that dreadful place we were all equals. There was no wealth, no titles, no envy to divide us.”[7]

Being a La Guardia

Reading her memoirs, it is easy to recognize the emotional and psychological strength and endurance that enabled her to survive her ordeal, which began when she was arrested by the Gestapo in Budapest, Hungary, where she lived with her Hungarian husband, on June 7, 1944. Her physical survival, however, had been only partly in her power.

Nazi documents used as evidence in the Eichmann trial confirmed that, as scholar Dr. Rochelle G. Saidel explained, Gemma was arrested and incarcerated “as a political hostage ordered by Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler and Adolf Eichmann because she was the sister of the powerful anti-Nazi mayor of New York.”[8]

Though Gemma did not practice Judaism, because her mother had been Jewish and she was married to a Jew, she was considered Jewish by both Jewish religious law and Nazi ideology. This and her age and health – she was 63 and on heart medication at the time of her arrest – meant that Gemma would normally have been immediately exterminated. Indeed, records show that this had been Eichmann’s original intent until he was convinced of her potential value for “political use.”[9]

Gemma also described in My Story how she was selected for the gas chamber in April 1945, but was spared at the last moment because, she was told directly, “they were fearful that some harm would come to the Germans in New York in reprisal.”[10]

“Being a La Guardia was the reason for my incarceration in Mauthausen and in Ravensbrück, but ultimately the name La Guardia saved my life and those of my daughter and grandson,” Gemma wrote.[11]

Unknown to her, one of her daughters and her baby grandson had also been imprisoned in Ravensbrück. The three were reunited in April 1945, shortly before they were removed from the concentration camp and briefly imprisoned in a Gestapo prison in Berlin, which was being bombarded by the Allies. When they were released in early May, they were left to their own devices in the unfamiliar and bombed-out city.

“I must confess that, ironically, this was the worst moment of my imprisonment—we were free and we did not know where to go. Bombs were falling above our heads, the great noise of combat thundered around us, houses were burning,” Gemma recalled.[12]

Over the next two years, Gemma, her daughter and grandson survived as displaced persons, first in Berlin, then in Copenhagen. Once again, her relationship to Fiorello La Guardia was both a help and a hindrance of sorts. By the summer of 1945, she had established communication with her brother, who was then serving the final months of his third term as Mayor of New York City. Although he provided financial support and promised to help her in any way he could, he made it clear that she would not be given preferential treatment because, he wrote to her, “your case is the same as that of hundreds of thousands of displaced people.”[13]

Just Another Survivor

Rather than being cold-hearted, Mayor LaGuardia seems to have been living up to his reputation as a scrupulously-honest man. Although she was born in the United States, Gemma had lost her U.S. citizenship when she married Herman Gluck, a Hungarian citizen, in 1908. Her daughter and grandson were both Hungarian citizens, with no rights to U.S. citizenship. The three survivors could not simply be repatriated to the U.S., and LaGuardia would not permit any special exceptions being made when so many people needed help.

His stance remained firm after he was appointed Director General of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) in March 1946. As the head of an international organization responsible for managing hundreds of post-war DP (displaced persons) camps around Europe and the repatriation of millions of refugees, LaGuardia was no more inclined to give special status to his family than he had been previously.

“He informed us that he was doing all within his power to get us to the United States, but that we would simply have to wait our turn in the visa quotas,” Gemma wrote her brother told her in 1946. “He could not treat us as if we were any more important than the thousands of other displaced persons who were waiting to get to America.”[14]

But both brother and sister were resourceful and persistent individuals, respectively overcoming hurdles and surviving until, finally, in May 1947, Gemma, her daughter and grandson all received permission to sail to the U.S. They arrived in New York Harbor on May 19, 1947.

Gemma, who was born in New York in 1881, before the Statue of Liberty had been erected, marveled at “that great bronze lady who stands at the gateway to America, holding high the torch of freedom, with the broken shackles of persecution at her feet.”

“I never dreamed that the true meaning of the Statue of Liberty would be revealed to me… when I returned to America as a weary, shattered survivor of the Holocaust the Nazis had unleashed on the lands of Europe. Only then did I see it in the same light as millions of other refugees have seen it.”[15]

For Gemma, the homecoming would have been bittersweet. She had regained her U.S. citizenship in the most tragic of ways: the death of her husband in Mauthausen. Her daughter Yolanda’s husband had also died in Mauthausen. Then, four months later, Gemma’s beloved brother Fiorello died of cancer. She remarks poignantly at the end of her memoir, “All of Fiorello’s plans for us vanished with his death.”[16]

Indeed, it is hard to fathom how she lived in obscurity in a low-income housing project in Queens for so many years, as monuments and memorials were raised to her brother, quite literally all around her. Even My Story seemed to quickly fade from the public consciousness, long out of print by the time it was discovered by Dr. Rochelle G. Saidel in 1980, while she was researching Ravensbrück concentration camp.

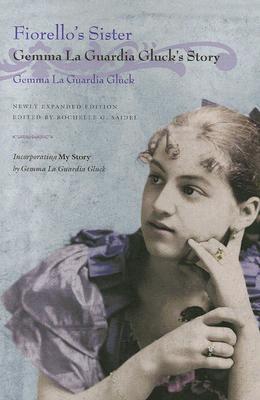

In her 2004 book, The Jewish Women of Ravensbrück Concentration Camp, Dr. Saidel brought Gemma La Guardia Gluck back to the historical record. She then painstakingly unearthed and gave new life to My Story in 2007 with a new edition, Fiorello’s Sister: Gemma La Guardia Gluck’s Story, filled with photos, personal letters and additional context. Yet, no major works and relatively little else has been written about this courageous and inspiring woman who, regardless of her connection to Fiorello La Guardia, is arguably worthy of greater attention and study.

In her 2004 book, The Jewish Women of Ravensbrück Concentration Camp, Dr. Saidel brought Gemma La Guardia Gluck back to the historical record. She then painstakingly unearthed and gave new life to My Story in 2007 with a new edition, Fiorello’s Sister: Gemma La Guardia Gluck’s Story, filled with photos, personal letters and additional context. Yet, no major works and relatively little else has been written about this courageous and inspiring woman who, regardless of her connection to Fiorello La Guardia, is arguably worthy of greater attention and study.

In My Story, Gemma wrote that she knew when she entered Ravensbrück in 1944, she would need to one day write a memoir about her experiences there because, “I feared there were still some people who didn’t believe all these unpleasant deeds to be true.”[17]

“I hope that this memoir will remind those people who too easily forget what happens when fear is the ruler of the land, and when men become less than men.”[18]

Nearly 75 years later, both her fear and her hope resonate. Deniers and demagogues sit in high office. Nationalist and populist ideologies grow strong on people’s fear and uncertainty. The same forces that were pushed to the darkest margins following the Second World War are resurgent.

We continue to ignore stories like Gemma’s at our own peril.

***

Featured image: Memorial statue by German artist Fritz Cremer located at the site of Mauthausen concentration camp. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

[1] Gluck, Gemma. My Story. 1961. Rpt. as Fiorello’s Sister: Gemma La Guardia Gluck’s Story. Kindle Edition. Ed. Rochelle G. Saidel. Syracuse University Press, 2007. 67.

[2] Because Fiorello LaGuardia signed his surname as one word instead of two, it is spelled this way in association with him, though not Gemma. LaGuardia Airport uses the surname as LaGuardia himself did.

[3] Gluck 46

[4] ibid 19-20

[5] ibid 42

[6] ibid 44

[7] ibid 48

[8] Saidel, Rochelle G. “Prologue.” Fiorello’s Sister. 7-8

[9] Schneiderman, S.L. “Preface to the Original Edition [of My Story].” Rpt. in Fiorello’s Sister.

[10] Gluck 79-80

[11] ibid 123

[12] ibid 89

[13] LaGuardia, Fiorello. Letter to Gemma La Guardia Gluck. 31 Oct. 1945. Fiorello’s Sister. 142.

[14] Gluck 120

[15] ibid 9

[16] ibid 122

[17] ibid 67

[18] ibid 123

[…] [9] ibid, 1-6. See, for example, my blog post from 2018 on Gemma LaGuardia Gluck. […]

LikeLike