While many, if not most, memes are harmless fun, others foster misogynistic stereotypes, willfully distort and obscure history, and spark abusive behavior on social media. Six years ago, I came across one of these and decided to uncover the real history behind the photo, never expecting the effect it would have.

Victoria Martínez

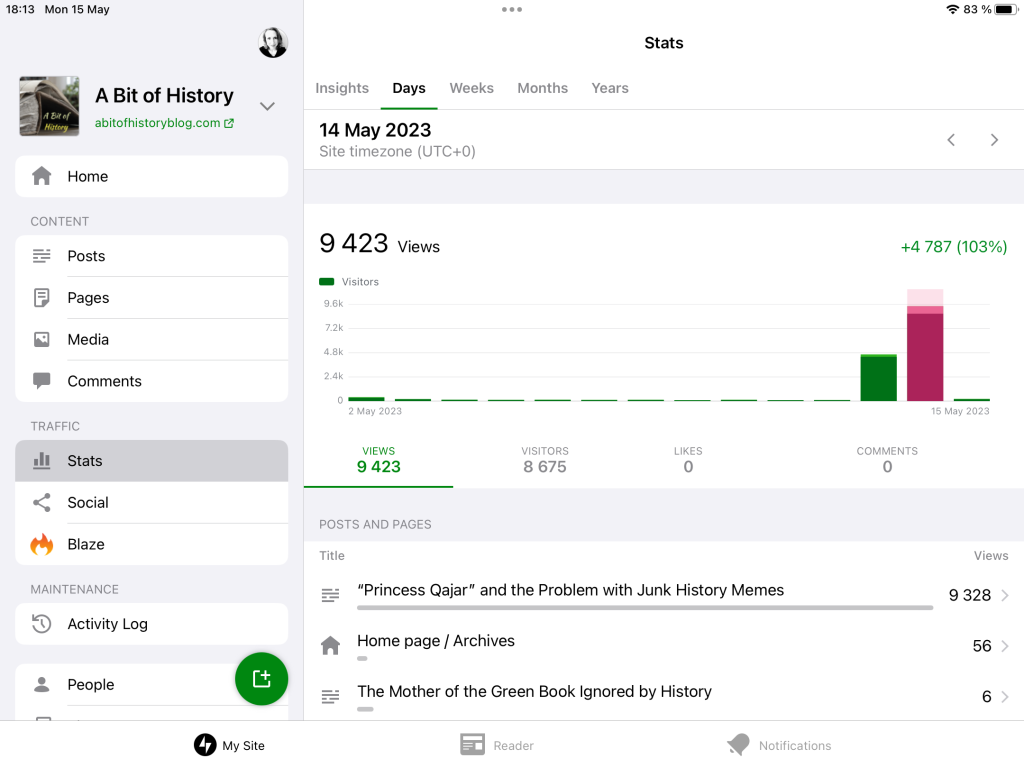

Roughly once every four to six weeks, WordPress sends me an enthusiastic notification about this blog that reads: “Your stats are booming!”. But this alert is not because of new blog posts. This is the first blog post I have made since the spring of 2019, just before I began working on my Ph.D. Instead, it’s a signal that the misogynistic viral “Princess Qajar” memes are making the rounds again on social media, and people want to know if 13 men really killed themselves for a plus-sized Persian princess with facial hair.

As of this writing, my blog post titled “‘Princess Qajar’ and the Problem with Junk History Memes,” which I published in December 2017, has been viewed on my blog over 1,200,000 times, as well as nearly 650,000 times on Medium, where it is cross-posted, has appeared in numerous authorized translations (and at least a few unauthorized ones), has been cited in international newspaper articles and blog posts, has appeared in at least one YouTube video, and so on.

An indicator that the “Princess Qajar” meme is making the rounds on social media once again.

I’m not being disingenuous when I say that I never imagined it would get this kind of response when I posted it. I wrote it because I was (and still am) angry that misogynistic trolls were targeting women now and in history through a series of memes that were most definitely not innocent and humorous. I decided that the best response was to channel my feelings using my skills as a historical researcher and writer and to the history of the women pictured in the memes for the benefit of anyone else who cared to know it. Judging by the response, a lot of people have cared to know.

It is incredibly gratifying that something I wrote has reached such a wide audience for what I would call the ‘right’ reasons. I’m equally gratified that as time passes I get the WordPress notifications less frequently. I interpret this at least partly as a signal that the memes (there have been several versions) are gradually losing some of their viral power, perhaps at least partially due to the wide proliferation of my blog post and its diffusion in other media. But these feelings are also mixed with a sense of continued frustration; not just about the content of the memes, but also about how and why distorting and damaging memes like this and other content disguised as history proliferates in the first place.

While I was actively writing for my blog I was what could be described as a “non-academic” historian; that is, I was writing from outside academia and for primarily non-academic audiences. But I had both access to academic scholarship and experience deciphering it for use in the history articles I wrote for everyday readers. The access and the skill were useful for my blog post on the “Princess Qajar” memes since some of the best sources of information were academic works and digital sources unlikely to be known or easily found or accessible to a broader public audience. My blog post did not create new knowledge. It made existing knowledge accessible to a wider audience. And this is where much of my continued frustration lies. Had these academic sources been accessible, affordable, and/or known to the broader public, the malicious “Princess Qajar” memes might not have gone viral in the first place, or at least not to the extent they did.

The Covid-19 pandemic highlighted just how dangerous misinformation can be. In early 2020, the director-general of the World Health Organization said, “We’re not just fighting an epidemic; we’re fighting an infodemic.” Soon after, an article published in Psychology Today put the responsibility for this Covid-19 ‘infodemic’ in the collective lap of academics. The question posed by the author, an academic, was: “Why do scientists fail to keep the spread of disinformation surrounding the coronavirus at bay?” At the heart of the problem, he suggests, is that academics do not write enough for the public because the academic system compels them to publish in academic journals that relatively few people (including academics) ever actually read. At least part of the solution to stopping the spread of misinformation about Covid-19, he argued along with others, is for academics to make an effort to publish in popular media, where their knowledge can have a wider impact. The same is true of other forms of misinformation, including racist, misogynistic memes.

I’m not sure how long the “Princess Qajar” memes had been online before I saw them and responded with my blog post, but certainly long enough that they were not only viral but also virulent, as the comment threads demonstrated. Among the vile sexist, racist, and xenophobic comments and the justifiably angry responses to these were attempts to make some historical sense of the photographs and captions that comprised the memes. But these attempts were rarely grounded in any evidence, not to mention any sources that could solidly refute the claims the memes made. Had information from the sources I cited been readily available in the popular press, more people would have been able to ‘fact-check’ the memes’ claims on social media and perhaps effectively make the memes themselves a mockery instead of the historical women they depict. This is exactly the gap my blog article filled.

Granted, not even the wide diffusion of what I wrote has made the memes obsolete. But, as my blog metrics show, they do seem to pack far less of a punch than they used to now that people can refer to solid sources to refute the claims they make rather than just fruitlessly responding to vitriolic comments. The response to my blog post also suggests that there is a strong public appetite for accessible academic knowledge, especially where viral misinformation is involved. The success of online publications such as The Conversation and a growing number of academic blogs are wider indicators of this appetite. But while I am thrilled about these developments, I think that the knowledge gap that allows misinformation to thrive can be only partly filled by academics simply publishing more frequently in popular media.

What is required to effect greater change, in my opinion, is improved cooperation and collaboration between academics and their non-academic counterparts (i.e., journalists, bloggers, and other content creators, public historians, etc.) who do or can make sense of academic scholarship in the content they publish in popular media, as I did with my blog post on the “Princess Qajar” memes before I was an academic. This cooperation and collaboration could of course be undertaken through direct interaction, but I think it should also involve taking steps that facilitate better access and understanding of existing research.

For starters, it is vital that academics and non-academics alike work to overcome the inaccessibility of academic scholarship created by needlessly complex writing and academic journal paywalls. Academics can help make this possible by writing in a more accessible way and by choosing to publish open access. Non-academics can help by going to public or university libraries where academic research can be accessed, by properly citing and linking to academic texts when they publish content, and by joining academic institutions and public policy organizations in the push for increased open access. Of course, direct collaboration between academic and non-academic historians and other researchers is also essential. This can be accomplished in a variety of ways, from organizing and participating in joint workshops and conferences (such as this one that I organized), to creating collaborative online platforms to share and discuss research topics, to writing articles and other content together for publication in various media.

Through these and other efforts, I firmly believe that academics and non-academics can together play an important role in making academic knowledge accessible to a wider public and thus help to bridge the knowledge gap that damaging viral memes and other forms of misinformation both expose and exploit.

I am pretty certain that nothing I write in my current capacity as an academic will come even close to being read by as many people as my blog post on the “Princess Qajar” memes. Perhaps nothing I write again will see such popular success. And, if academics and non-academics succeed in narrowing the knowledge gap that allows misinformation to thrive, blog posts like mine would be less likely to have such outsized success. I see this as a positive. It would be nice to one day wake up to the WordPress notification “Your stats are booming!” for a reason other than the resurgence of racist, misogynist, and xenophobic memes.

[…] ***An update of sorts on this blog post was published on August 10, 2023. See The Slow Death of the “Princess Qajar” Meme and How to (Maybe) Kill It Once and for All.*** […]

LikeLike